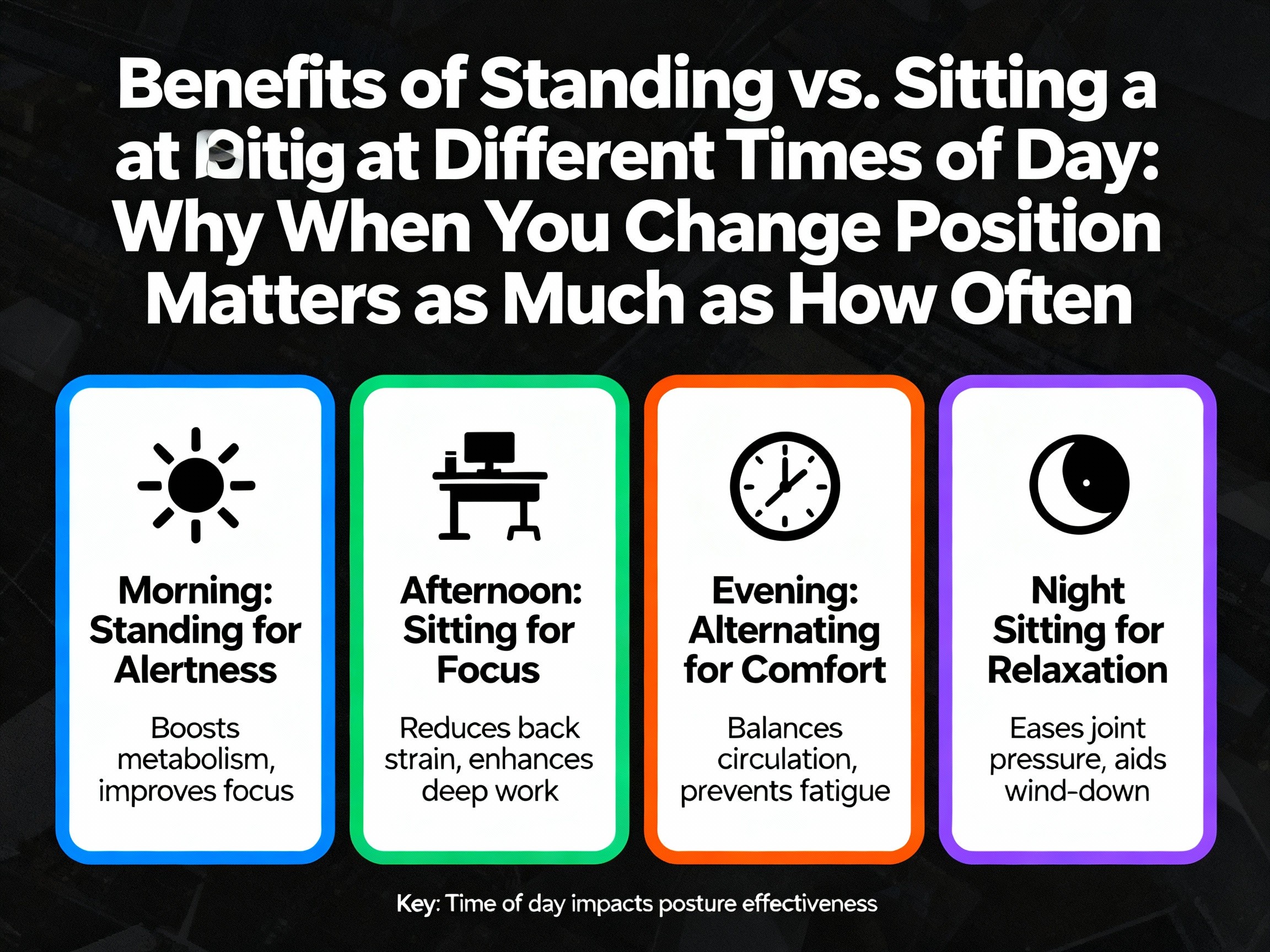

Imagine two office workers, both using standing desks and both alternating between standing and sitting throughout their workdays. They change positions with similar frequency, spending roughly equal total time on their feet. Yet one returns home energized and maintains stable energy through the afternoon, while the other battles crushing fatigue by mid-afternoon and struggles with evening restlessness that disrupts sleep. The difference between these outcomes doesn’t lie in how much they stand or sit, but in when they make these position changes. Your body’s response to standing versus sitting varies dramatically depending on the time of day, your recent meal timing, your current activity, and where you are in your natural energy cycle. Treating all standing time as equivalent, or assuming that sitting is uniformly harmful regardless of when it occurs, misses the sophisticated reality of how postural changes interact with your body’s temporal rhythms.

The standing desk revolution emerged from compelling research showing the health costs of prolonged sitting, sometimes dramatically called “sitting disease.” This research is genuine and important. Extended periods of uninterrupted sitting do indeed harm metabolic health, cardiovascular function, and longevity. However, the simplistic response of “just stand more” overlooks critical nuances about timing and context. Standing immediately after meals provides completely different metabolic effects than standing in a fasted state. Standing during your natural energy peaks supports different cognitive and physical outcomes than standing during circadian troughs. Standing while engaged in focused mental work affects your brain differently than standing during routine tasks. By understanding these temporal patterns and strategically timing your position changes, you can capture the maximum benefits of both sitting and standing while minimizing the downsides of each, creating a dynamic postural strategy that works with your biology rather than against it.

The Metabolic Dance: How Your Body Processes Position Throughout the Day

To understand why standing versus sitting produces different effects at different times, you need to grasp how your metabolism operates on multiple overlapping cycles. Your body doesn’t maintain a constant metabolic state from morning to evening. Instead, your metabolic rate, insulin sensitivity, glucose regulation, fat oxidation, and numerous other processes follow predictable daily rhythms influenced by your circadian clock, meal timing, activity patterns, and hormonal fluctuations. When you stand or sit, you’re not just adopting a static position but rather introducing a metabolic stimulus that your body interprets and responds to based on its current state and recent history.

Standing increases your metabolic rate compared to sitting, but not dramatically. Studies typically show standing burns roughly twenty to fifty more calories per hour than sitting, depending on your body weight and how actively you’re moving while standing. This modest caloric difference means that standing alone isn’t a weight loss strategy; you’d need to stand for many hours to burn off even a small snack. However, the metabolic benefits of standing extend far beyond simple calorie expenditure. Standing activates large postural muscles in your legs, core, and back, triggering cellular signaling cascades that influence glucose uptake, fat metabolism, and insulin sensitivity throughout your entire body. These effects prove particularly powerful in specific metabolic contexts, especially in the period following meals when your body processes incoming nutrients.

The Post-Meal Window: Your Most Important Standing Period

Research consistently demonstrates that standing after meals provides dramatically greater metabolic benefits than standing at other times. When you eat, your blood glucose rises as your digestive system breaks down food and releases sugars into your bloodstream. Your body must clear this glucose spike, either by shuttling glucose into cells for immediate energy use or by storing it as glycogen or fat. Standing after meals, particularly in the thirty-to-sixty-minute window following eating, substantially improves this glucose clearance process. The muscle contractions required for standing increase glucose uptake by muscle cells without requiring insulin, effectively reducing both the height and duration of your post-meal glucose spike. Studies show reductions of fifteen to twenty-five percent in glucose area-under-the-curve, meaning significantly less glucose exposure over time. This matters enormously because repeated large glucose spikes contribute to insulin resistance, inflammation, and metabolic disease progression. By standing during this critical post-meal window, you harness your body’s natural response to muscle activation, turning standing into a powerful metabolic intervention rather than merely a postural variation.

Morning Metabolism: Primed for Movement

Your metabolic state in the morning differs substantially from afternoon or evening, creating unique opportunities and considerations for standing versus sitting. After overnight fasting, your glycogen stores sit at relatively low levels, your insulin sensitivity is typically at its highest point of the day, and your body is primed for glucose uptake and utilization. Your cortisol levels peak in early morning, supporting alertness and metabolic activity. This morning metabolic profile means that standing during morning hours capitalizes on your body’s natural readiness for activity. Your muscles respond readily to the standing stimulus, glucose regulation operates efficiently, and your cardiovascular system handles the postural demands easily.

However, morning also presents considerations about meal timing and energy availability. If you exercise or stand extensively in a fasted state first thing in the morning, you might feel more fatigued than expected because your readily available energy stores remain depleted from overnight. For most people, a pattern of moderate morning activity including some standing, followed by breakfast, followed by more extensive standing during the post-breakfast window works well. This sequence allows you to capitalize on morning alertness while avoiding the fatigue that can come from excessive fasted standing. The key insight is that morning standing proves most valuable when timed around breakfast, creating a synergy between meal-related glucose regulation and the metabolic benefits of upright posture.

Afternoon Metabolic Shifts: Managing the Post-Lunch Response

The afternoon period, particularly the two to three hours following lunch, represents your day’s most critical window for strategic position management. Multiple factors converge to make this period both challenging and opportune. Your circadian rhythm naturally dips in early afternoon, creating the familiar post-lunch energy slump that has nothing to do with meal size or composition but rather reflects your biological programming. Simultaneously, you’re processing lunch, creating a glucose challenge that your body must handle. Your insulin sensitivity is lower in afternoon compared to morning, meaning the same meal produces a larger glucose spike. Research shows that glucose tolerance deteriorates progressively throughout the waking day, making afternoon the worst time metabolically for large carbohydrate-heavy meals.

This afternoon metabolic vulnerability makes post-lunch standing particularly valuable but also potentially challenging. Standing after lunch helps mitigate the glucose spike and counteracts the circadian alertness dip by increasing overall activation and preventing the deep sedentary state that exacerbates afternoon drowsiness. However, if you’re battling significant fatigue, standing might feel difficult and uncomfortable, potentially leading to poor posture or giving up quickly. The strategic approach involves using standing as a tool to push through the initial afternoon fatigue rather than surrendering to it, but doing so intelligently with appropriate support and breaks. Many people report that while standing initially feels harder during afternoon slump, pushing through for fifteen to thirty minutes often triggers a second wind that makes the rest of the afternoon more productive than if they’d remained seated throughout.

Evening Standing: Benefits and Sleep Considerations

Evening hours present unique trade-offs for standing versus sitting that many people overlook. On one hand, standing after dinner provides valuable metabolic benefits similar to post-lunch standing, helping manage what is often the largest meal of the day and the one most likely to cause problematic glucose elevation due to naturally lower evening insulin sensitivity. Standing during evening hours also prevents the completely sedentary collapse into couch and television that characterizes many people’s evenings, maintaining some level of activity and muscle engagement that supports metabolic health. For people who struggle with evening snacking, standing can help break the automatic eating patterns that emerge during prolonged evening sitting.

However, evening standing must be balanced against sleep preparation needs. Standing is activating, increasing heart rate, blood pressure, and overall arousal compared to sitting or lying down. If you stand extensively late into the evening, you might find it harder to wind down for sleep. Your body needs time to transition from active, upright wakefulness to the relaxed state conducive to sleep initiation. A reasonable approach involves standing during and after dinner for metabolic benefits, then gradually transitioning to sitting and eventually to more reclined relaxation positions as bedtime approaches. The timing of this transition depends on your individual sleep patterns and how long you personally need to wind down, but most people benefit from at least an hour of progressively less activating positions before attempting sleep.

Cognitive Performance: When Standing Helps or Hinders Mental Work

The relationship between standing and cognitive performance proves more complex than simple assumptions about increased blood flow improving brain function. While standing does increase circulation and overall arousal compared to sitting, these changes don’t uniformly enhance all types of mental work, and the cognitive effects of standing vary substantially based on time of day, task type, and your current energy state. Understanding these nuances helps you avoid the mistake of standing during work that requires your deepest focus while missing opportunities to use standing strategically for maintaining alertness during lower-priority or routine tasks.

Deep Work and Focused Attention: The Sitting Advantage

Research on cognitive performance during standing versus sitting reveals an interesting pattern: for tasks requiring sustained deep focus, complex problem-solving, or working memory manipulation, sitting typically produces better outcomes than standing. This might seem counterintuitive given standing’s benefits for alertness, but it makes sense when you consider what happens physiologically during standing. When you stand, part of your brain’s attention and your body’s resources must continuously engage in postural control, balance maintenance, and managing the increased cardiovascular demands of upright posture. These ongoing background processes consume cognitive resources that would otherwise be available for your primary mental task.

For shallow or routine cognitive work, this resource competition doesn’t matter much because you have cognitive capacity to spare. However, when you’re working at the edge of your mental abilities, engaging in creative problem-solving, writing complex material, learning difficult concepts, or performing intricate analysis, every bit of cognitive capacity matters. During these deep work periods, the slight cognitive cost of standing can mean the difference between breakthrough insights and frustrating struggle. This suggests a strategic principle: reserve sitting for your most demanding mental work, particularly during your personal peak cognitive hours which for most people occur in late morning. Use standing for routine tasks, meetings, email processing, and other activities that don’t push your cognitive limits. This task-position matching optimizes both metabolic health through adequate standing and cognitive performance through strategic sitting.

Alertness and Arousal: Standing as a State Management Tool

While standing might slightly reduce peak cognitive performance on demanding tasks, it provides powerful benefits for managing your arousal and alertness levels throughout the day. When you feel drowsy, unmotivated, or mentally foggy, standing triggers a cascade of changes that increase arousal: heart rate elevates, blood pressure rises, stress hormones increase slightly, and your overall activation level shifts upward. This arousal boost doesn’t necessarily make you smarter, but it does make you more awake, which proves invaluable during times when your primary challenge involves staying alert rather than thinking deeply.

The afternoon energy dip represents the perfect application of standing for arousal management. During the two-to-four PM window when your circadian rhythm naturally dips and post-lunch digestion compounds the effect, simply remaining awake and functional can feel challenging. Standing during this period won’t make it your most brilliant thinking time, but it will prevent the semi-conscious drifting and complete loss of productivity that occurs when you sit through afternoon fatigue. The physical act of supporting your own body weight maintains a baseline level of engagement that sitting eliminates. For tasks that must happen during this low-energy window, standing transforms barely-functional zombie mode into adequately-alert working mode, even if you’re not achieving peak performance. Similarly, standing during late afternoon or evening work sessions helps maintain alertness when your body naturally wants to wind down for the day.

Creative Thinking: Movement and Ideation

An interesting exception to the sitting-for-deep-work principle emerges for creative ideation and divergent thinking. Multiple studies suggest that walking and movement facilitate creative idea generation compared to sitting, possibly because the physical movement and varied sensory input help break mental fixation and encourage novel associations. While these studies typically examine walking rather than standing, standing provides more opportunity for natural movement, fidgeting, and position shifting than sitting does. When you stand, you naturally move more, shifting weight, adjusting posture, and occasionally walking a few steps. This increased movement might support creative thinking even if it slightly reduces analytical focus.

This suggests a nuanced approach to matching position with cognitive task type. For convergent thinking where you’re working toward a specific solution using logical analysis, sitting optimizes focus. For divergent thinking where you’re generating many possibilities and making unexpected connections, standing with freedom to move supports ideation. For complex creative work involving both generation and refinement, you might alternate positions across work phases: stand while brainstorming and exploring possibilities, then sit for the focused work of developing and executing your best ideas. This dynamic approach recognizes that creative work isn’t monolithic but rather involves different cognitive modes that benefit from different physical states.

The Fatigue Threshold: When Standing Becomes Counterproductive

Standing provides benefits only up to the point where it causes significant fatigue that degrades your overall function. If you stand so long or at such inopportune times that you develop substantial physical discomfort, mental fatigue, or reduced work output, you’ve crossed from beneficial standing into counterproductive standing. This threshold varies enormously between individuals based on fitness level, age, existing health conditions, and standing experience. Someone who’s been using a standing desk for months might comfortably stand for sixty to ninety minutes at a stretch, while someone new to standing might need to sit after twenty to thirty minutes. The key is listening to your body’s signals rather than pushing through to meet arbitrary standing targets. Discomfort, decreased focus, irritability, or declining work quality all suggest you’ve reached your current standing threshold and should sit before these costs accumulate further. Progressive adaptation allows you to extend your comfortable standing duration over weeks and months, but forcing excessive standing before your body is ready typically backfires.

Practical Standing Protocols: Building Your Daily Pattern

Understanding the principles of timing standing and sitting means little without concrete strategies for implementation. The following protocols provide structured approaches you can adopt or adapt based on your particular schedule, work demands, and personal responses. Remember that these represent starting frameworks rather than rigid prescriptions; the goal is discovering patterns that work for your unique circumstances while honoring the general principles about metabolic timing and cognitive load.

The Meal-Anchored Protocol: Metabolic Optimization

This approach prioritizes standing during the critical post-meal windows when metabolic benefits are greatest. Begin standing about fifteen to thirty minutes after finishing each main meal, continuing for thirty to ninety minutes depending on your tolerance and work demands. For most people working a standard schedule, this creates three main standing periods: mid-morning following breakfast, early afternoon following lunch, and early evening following dinner. Between these meal-anchored standing periods, sit as needed for focused work, particularly during late morning when your cognitive performance peaks naturally.

The beauty of meal-anchored standing lies in its natural trigger: you’ve just eaten, making the transition to standing feel purposeful and automatic rather than arbitrary. Post-meal standing also tends to feel more comfortable than standing while hungry, as the recent food provides energy that supports sustained upright posture. If you struggle to remember to change positions, the meal-anchored approach provides built-in reminders tied to necessary daily events. The main challenge comes if you eat lunch at your desk while working, as this creates temptation to remain seated afterward. Consider taking actual meal breaks away from your desk, then returning to stand for post-meal work. This separation reinforces the standing habit while providing mental breaks that benefit cognition independent of position changes.

The Task-Based Protocol: Cognitive Optimization

Rather than timing positions around meals or arbitrary intervals, the task-based approach matches position to work type. Sit for deep focus work including writing, analysis, complex problem-solving, learning, and any tasks requiring your peak cognitive performance. Stand for routine administrative work, email processing, phone calls, video meetings, casual conversations, brainstorming sessions, and other activities that don’t demand maximum mental capacity. This creates a natural rhythm where you sit during your most valuable thinking time and stand during the necessary-but-less-demanding portions of your work.

The task-based protocol optimizes for productivity and cognitive performance, potentially at some expense to metabolic benefits if your deep work happens to cluster around meal times. You can partially address this by trying to schedule deep work away from immediate post-meal periods, or by taking brief standing breaks during extended sitting sessions even if you don’t change your primary work position. The advantage of task-based positioning lies in its alignment with work flow, making position changes feel natural rather than disruptive. When you finish writing and shift to email, standing for that transition reinforces the mental shift between work modes while providing physical variation. Many people find this protocol easiest to maintain long-term because it integrates seamlessly with existing work patterns rather than imposing additional structure.

The Rhythm Protocol: Regular Alternation

For people who prefer structure and regular patterns, the rhythm protocol alternates standing and sitting at fixed intervals regardless of meals or tasks. A common pattern involves sitting for forty-five to sixty minutes, then standing for fifteen to thirty minutes, repeated throughout the day. This creates predictable position changes that become habitual through repetition. Set timers or use apps that remind you when to change positions, removing the burden of remembering from your conscious awareness. The regular alternation prevents extended periods in either position, distributing the benefits and costs of each across your day.

The rhythm protocol works best when you modify the basic pattern to incorporate time-of-day considerations. You might use forty-five minute sitting intervals during morning focused work, shorter thirty-minute sitting intervals during afternoon when standing provides greater benefit, and progressively longer sitting intervals as evening approaches and you prepare for bed. You could maintain the regular alternation structure while adjusting the sitting-to-standing ratio across the day, perhaps using 2:1 ratios in morning but 1:1 ratios after lunch when standing becomes more metabolically important. This time-sensitive rhythm protocol combines the structure of regular intervals with the flexibility of adapting to your body’s changing needs throughout the day.

Transition Strategies: Managing Position Changes Effectively

The mechanics of how you transition between standing and sitting significantly influence both your comfort and the effectiveness of position changes. Abrupt transitions that interrupt focus or create physical strain reduce adherence to any standing protocol. Thoughtful transition strategies make position changes feel natural and even beneficial rather than disruptive and uncomfortable. Understanding what happens in your body during transitions helps you manage them more effectively.

The Stand-Up Transition: Managing Postural Adjustment

When you first stand after sitting for a period, your cardiovascular system must rapidly adjust to meet the new demands of upright posture. Blood that pooled in your legs during sitting must be redistributed, your heart rate increases, blood vessels constrict, and various compensatory mechanisms activate to maintain blood pressure to your brain. Most people handle this transition seamlessly, but some experience orthostatic intolerance, where standing causes dizziness, lightheadedness, or brain fog. This proves particularly common when standing immediately after meals, when blood is diverted to your digestive system, or when you’re dehydrated.

Manage stand-up transitions by rising gradually rather than leaping to your feet. Take a moment to shift position while still seated, perhaps doing some ankle flexes or leg movements to activate muscle pumps before standing. Once standing, don’t remain completely still; subtle movements like weight shifting, calf raises, or walking in place help your muscle pump system assist with blood circulation and make the cardiovascular adjustment easier. If you feel dizzy or uncomfortable upon standing, this signals you should either sit back down and try again more gradually, or stand but move your legs actively to support circulation. Over time, regular standing strengthens the cardiovascular adaptations that make these transitions smoother, but respecting your current capacity prevents the discouraging experiences that undermine long-term adherence.

Desk Height and Ergonomic Considerations

Proper desk height proves critical for comfortable standing. Your elbows should rest at approximately ninety degrees with your monitor at or slightly below eye level to avoid neck strain. Many people initially set standing desks too high, creating shoulder tension and arm fatigue. Others set them too low, causing them to hunch forward. Take time to properly adjust your standing desk height, and recognize that optimal height when standing differs from optimal height when sitting, requiring adjustment when you change positions. Electric adjustable desks make this easy; manual adjustments take more effort but remain worthwhile for the comfort benefits.

Beyond desk height, consider your entire standing ergonomics. An anti-fatigue mat provides cushioning that reduces leg and back strain compared to standing on hard floors. Supportive shoes matter enormously; avoid standing in unsupportive footwear that creates foot, knee, or back pain. Some people benefit from a small footrest or stool that allows occasional leg elevation or position variation while standing. Your keyboard and mouse positioning should allow relaxed arms and neutral wrist positions. Poor ergonomics during standing causes discomfort that makes you sit prematurely, while good ergonomics allows extended comfortable standing that actually provides the intended benefits.

Movement While Standing: Active vs. Static

Completely static standing, where you remain in one fixed position without movement, actually provides fewer benefits and causes more discomfort than active standing where you allow natural fidgeting and position shifting. Your body isn’t designed for stationary standing any more than it’s designed for stationary sitting. Guards who must stand still for long periods often struggle with fatigue and even fainting, while people who stand but move around regularly report much less discomfort. This movement doesn’t need to be dramatic; simply shifting your weight from leg to leg, occasionally walking a few steps, or doing subtle stretches makes standing far more sustainable.

Some standing desk users incorporate additional movement tools like balance boards, treadmill desks, or cycling devices. These can provide benefits but also introduce complexity and potential downsides. Treadmill desks require careful speed management to avoid interference with fine motor tasks or cognitive work. Balance boards can be fatiguing and distracting. The simplest and most universal approach involves just allowing yourself to move naturally while standing rather than forcing yourself into rigid stillness. Give yourself permission to pace, stretch, shift weight, or adjust position whenever you feel the impulse. This natural movement represents your body’s wisdom about what it needs for comfort, not restlessness that should be suppressed.

Progressive Adaptation: Building Standing Capacity Over Time

If you’re new to regular standing, begin conservatively and build capacity gradually rather than immediately attempting extended standing periods that leave you exhausted and discouraged. Start with just fifteen to twenty minutes of standing at a time, perhaps two or three times daily. Even these brief standing periods provide metabolic benefits while allowing your body to adapt. Over subsequent weeks, gradually extend your standing duration by five to ten minutes per session as comfort permits. Within four to eight weeks, most people can comfortably stand for forty-five to sixty minutes at a stretch, with some able to sustain even longer periods. This progressive approach allows the musculoskeletal adaptations, cardiovascular conditioning, and postural muscle strengthening that make extended standing comfortable. Forcing excessive standing before these adaptations develop typically backfires, causing pain or fatigue that makes you abandon standing entirely. Patience during the adaptation period pays dividends in long-term sustainability.

Individual Factors: Who Benefits Most and Who Should Exercise Caution

While standing provides benefits for most people, individual factors substantially influence how much standing helps, what timing works best, and whether any precautions are needed. Understanding your personal standing profile helps you customize recommendations rather than blindly following generic advice that might not suit your circumstances. Age, fitness level, health conditions, occupation, and personal preferences all shape optimal standing strategies.

Metabolic Health Status: Maximum Benefit Population

People with impaired glucose tolerance, pre-diabetes, type 2 diabetes, or metabolic syndrome gain the most dramatic benefits from strategic standing, particularly post-meal standing. Research shows that these populations experience larger improvements in glucose control from standing compared to metabolically healthy individuals. This makes sense because they face greater baseline challenges with glucose regulation that standing helps mitigate. If you fall into this category, prioritizing meal-anchored standing becomes especially important. The thirty-to-sixty-minute post-meal standing window isn’t just a nice-to-have but rather a powerful intervention that can meaningfully affect your glucose patterns and potentially slow metabolic disease progression.

However, these same individuals might initially find standing more challenging due to cardiovascular deconditioning or excess weight that makes prolonged standing uncomfortable. Start very gradually with short standing periods, perhaps just ten to fifteen minutes post-meal initially. Use whatever supports you need for comfort, including anti-fatigue mats, supportive shoes, or even leaning positions that reduce leg loading. The metabolic benefits prove worth the adaptation process, but pushing too hard too fast increases injury risk and reduces adherence. Consider standing while doing less physically demanding tasks initially, saving more active or demanding work for sitting periods until your standing capacity improves.

Age Considerations: Young Workers vs. Older Adults

Younger workers often tolerate standing more easily and recover from standing fatigue more quickly than older adults. Their generally better cardiovascular function, stronger postural muscles, and less likely joint problems make standing feel more natural and comfortable. This doesn’t mean young people should stand continuously; the principles of timing and variation still apply. But it does mean younger individuals can likely progress faster in building standing capacity and may tolerate longer standing periods during peak times like post-meal windows.

Older adults benefit substantially from standing’s metabolic effects and the maintenance of balance capacity that standing requires and develops. However, age-related changes in cardiovascular regulation, potential joint issues, reduced muscle mass, and balance concerns require more caution. Older adults should progress more conservatively in building standing time, may need more frequent position changes between standing and sitting, and should pay particular attention to proper ergonomics and supportive equipment. Balance and fall risk become relevant considerations; if balance is compromised, ensure your standing arrangement provides nearby supports you can grab if needed. The metabolic and functional benefits of regular standing prove particularly valuable for healthy aging, but the approach must be adapted to accommodate age-related changes.

Health Conditions Requiring Modified Approaches

Certain health conditions require modified standing strategies or, in some cases, make standing inadvisable without medical guidance. Cardiovascular conditions including orthostatic hypotension, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, or severe heart failure can make standing problematic or even dangerous. Peripheral artery disease or severe varicose veins might worsen with prolonged standing. Severe arthritis or chronic pain conditions affecting legs, hips, or back may make extended standing impractical. Pregnancy, particularly in later stages, changes cardiovascular demands and balance in ways that affect standing tolerance.

If you have any significant health condition, consult your healthcare provider before implementing substantial increases in standing time. Many conditions don’t preclude standing but rather require modifications: shorter standing periods, more gradual progression, use of compression garments, careful attention to hydration, or specific ergonomic accommodations. The goal is capturing standing’s benefits while avoiding exacerbation of existing health issues. In some cases, the metabolic benefits of even brief standing might prove valuable despite limitations on duration. Work within your capacities rather than abandoning standing entirely because you can’t meet ideal recommendations designed for healthy individuals.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Even people who understand the principles of strategic standing often make implementation mistakes that reduce benefits or create problems. Recognizing these common pitfalls helps you avoid them, making your standing practice more effective and sustainable. Many of these mistakes stem from overzealousness or misapplication of general advice without considering individual context and timing principles.

The All-or-Nothing Trap

Perhaps the most common mistake involves taking an extreme position, either attempting to stand all day or giving up on standing entirely after initial discomfort. Some people get standing desks and immediately try to stand for their entire workday, viewing sitting as something to be eliminated rather than strategically reduced. This typically leads to exhaustion, pain, and eventual abandonment of standing. The opposite mistake involves trying standing for a few days, experiencing some discomfort or inconvenience, then declaring it doesn’t work and returning to full-time sitting. Both extremes miss the nuanced reality that optimal health comes from strategic variation, not from maximizing either position.

The solution involves embracing standing as a tool to be used strategically rather than a virtue to be maximized. Aim for a reasonable distribution, perhaps thirty to forty percent of waking hours spent standing for most people, concentrated during the times when standing provides maximum benefit. Accept that some sitting is not only fine but actually preferable for certain tasks and times. This balanced approach proves far more sustainable long-term than extreme attempts at constant standing or reactive abandonment after bad initial experiences.

Ignoring Time-of-Day Effects

Many people stand when convenient rather than when most beneficial, missing the powerful metabolic effects of post-meal standing while standing extensively during morning hours when sitting would support better cognitive work. This random timing approach captures some benefits of position variation but misses the opportunity to align standing with your body’s temporal rhythms. The fix is simple but requires attention: prioritize standing during the thirty-to-ninety-minute window after meals, particularly after lunch when both metabolic vulnerability and natural energy dips make standing especially valuable. Use afternoon standing even if it feels harder, recognizing that the difficulty reflects exactly why this timing matters more.

Poor Ergonomics and Posture

Standing with poor posture or ergonomics turns a beneficial practice into a harmful one. Common problems include standing desks set at wrong heights, leading to hunched shoulders or strained necks; standing in unsupportive shoes that create foot or back pain; completely static standing without any movement variation; and allowing fatigue to degrade posture into slouched or asymmetric positions that create strain. Each of these transforms standing from health-promoting to harm-inducing. Address ergonomics systematically: invest in an anti-fatigue mat, wear supportive footwear, adjust desk height properly for both sitting and standing, use monitor arms to position screens optimally, and allow natural movement while standing. Good ergonomics makes standing comfortable enough to sustain, while poor ergonomics guarantees eventual problems.

Neglecting Progressive Adaptation

Impatience drives many people to stand for durations their bodies aren’t yet ready to handle comfortably, creating fatigue, pain, or injury that could have been avoided through gradual progression. Your body needs time to strengthen postural muscles, adapt cardiovascular responses, condition feet and legs, and develop the unconscious adjustments that make standing feel natural. Forcing this process through sheer willpower typically backfires. Instead, start with standing durations that feel easily manageable, even if they seem trivially short. Build incrementally, adding five to ten minutes per week as comfort permits. This patient approach feels slower initially but actually reaches sustainable high-duration standing faster than aggressive approaches that lead to setbacks and recovery periods.

Your Personal Standing Strategy: Getting Started

Begin implementing time-aware standing by choosing one protocol that resonates with your primary goals and daily structure. If metabolic health concerns drive your interest, adopt the meal-anchored protocol. If cognitive performance and productivity matter most, try the task-based approach. If you prefer structure and habit formation, start with the rhythm protocol. Give your chosen protocol at least two weeks of consistent implementation before evaluating results or making changes. Track your experience in a simple log noting standing duration, timing, energy levels, work quality, and physical comfort.

Start conservatively with standing duration, particularly if you’re new to regular standing or have any health considerations. Initial standing periods of fifteen to twenty minutes two to three times daily provide real benefits while remaining manageable for most people. Prioritize post-lunch standing even in this limited initial phase, as this timing provides disproportionate metabolic returns. As you adapt, gradually extend standing duration and frequency while maintaining focus on strategic timing rather than simply maximizing total standing time.

Invest in basic ergonomic supports that make standing comfortable: an anti-fatigue mat, a properly adjustable desk or converter, supportive footwear, and correct monitor positioning. These upfront investments dramatically affect your long-term adherence and comfort. Poor ergonomics guarantees eventual problems that undermine even the best-intentioned standing practice. Consider your standing setup as important as any other health investment, deserving attention and appropriate resources.

Remember that standing is a tool for health and performance, not a moral imperative or competitive sport. There’s no award for standing the longest or most frequently. Your goal is finding the pattern that provides maximum benefit in your particular circumstances while remaining sustainable long-term. This might mean less total standing than ideal recommendations if you have limitations, or it might mean more standing than minimum guidelines if you find it particularly beneficial. Let your own experience and outcomes guide your practice rather than rigidly following anyone’s prescriptions, including mine. The principles of timing, progression, and strategic variation provide the framework; you fill in the specifics based on your unique biology, preferences, and life context.

“The human body is the best picture of the human soul.” Ludwig Wittgenstein’s observation reminds us that physical practices like strategic standing aren’t merely about biological health markers but reflect and shape our entire relationship with embodiment and daily living. When we learn to honor our body’s temporal rhythms, we practice a form of self-respect that extends far beyond any single health metric.

Resources for Further Learning

For readers interested in exploring the science of standing, sitting, and metabolic health more deeply, these evidence-based resources provide valuable insights:

- British Journal of Sports Medicine publishes research on sedentary behavior and its health effects, including numerous studies on standing interventions

- Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise features studies on metabolic responses to postural changes and timing effects

- Get Up! Why Your Chair Is Killing You by James Levine explores the science behind sedentary behavior and movement

- Diabetes Care journal publishes research on glucose control strategies including standing interventions

- Occupational Ergonomics journal addresses practical workplace implementation of standing desks and position variation

The timing of when you stand versus sit matters as much as how much you stand in total. By aligning your postural changes with your body’s natural metabolic and cognitive rhythms, you transform standing from a simple alternative to sitting into a sophisticated tool for optimizing health and performance. The post-meal window, the afternoon energy dip, your peak cognitive hours, and your evening wind-down all present unique opportunities to use standing and sitting strategically. Rather than viewing standing as universally superior to sitting, recognize that each position serves different purposes at different times. Your challenge is learning to read your body’s signals, understanding the temporal patterns that govern your responses, and building sustainable practices that honor both your health needs and your real-world constraints. The art of strategic positioning throughout the day represents not just a workplace intervention but a form of somatic wisdom that improves your relationship with your body across all contexts.