Your body operates on rhythms you rarely notice consciously, yet these patterns govern everything from when you feel hungry to when your mind achieves peak clarity. Among these rhythms, one stands out for its profound impact on work performance: the ninety-minute cycle known as the ultradian rhythm. This isn’t some new productivity hack dreamed up by efficiency experts but rather a fundamental biological pattern that has been shaping human behavior since long before we invented offices, computers, or the modern workday. Every hour and a half, your brain naturally transitions between states of high and low capacity, creating windows of opportunity for focused work followed by periods demanding rest and recovery.

Think of your energy throughout the day like ocean waves. Just as waves build to a crest before retreating back into the sea, your mental capacity rises to peaks of intense focus and clarity, then necessarily recedes into valleys where concentration becomes difficult and mistakes multiply. Most people fight against these valleys, pushing through fatigue with caffeine and willpower, believing that continuous effort yields continuous results. This approach not only feels exhausting but actually produces diminishing returns as you spend increasingly more energy to accomplish increasingly less work. When you learn to recognize and respect your ninety-minute cycles, you can position your most demanding tasks during your natural peaks and allow yourself genuine recovery during the valleys, ultimately accomplishing more while feeling significantly less depleted.

The Science Behind Your Brain’s Natural Rhythm

Before we explore how to apply the ninety-minute cycle to your work, you need to grasp what’s actually happening inside your brain during these rhythms. The term ultradian comes from Latin roots meaning “beyond a day,” distinguishing these shorter cycles from the better-known circadian rhythm that operates across twenty-four hours. While your circadian rhythm determines when you feel sleepy or alert across the entire day, ultradian rhythms create shorter waves of capacity within each waking period. These cycles govern not just your alertness but also hormone levels, body temperature, hunger, and most importantly for our purposes, your cognitive performance.

During the first portion of each ninety-minute cycle, roughly the first fifty to sixty minutes, your brain operates with enhanced capacity. Your prefrontal cortex, the region responsible for complex thinking, planning, and focus, functions at its peak efficiency during this window. Neural networks fire with optimal coordination, neurotransmitters flow at ideal concentrations, and your working memory can juggle multiple pieces of information simultaneously. This is when difficult problems suddenly make sense, when you write with unusual clarity, or when you lose track of time because you’re so absorbed in your task. Researchers studying these patterns have documented measurable improvements in reaction time, problem-solving speed, and creative insight during these peak phases.

Why Ninety Minutes? The Sleep Connection

The ninety-minute pattern didn’t emerge randomly but reflects deep aspects of how your nervous system functions. During sleep, you cycle through different stages approximately every ninety minutes, moving from light sleep through deep sleep and into REM dreaming before the cycle repeats. This same basic architecture persists during waking hours, though manifesting differently. Your brain alternates between states optimized for focused external engagement and states requiring restoration and internal processing. Some scientists theorize this rhythm evolved to balance the competing demands of hunting, gathering, and socializing against the need for rest and recovery, creating a natural pacing that prevented exhaustion while maximizing effectiveness. Modern work often ignores this ancient pattern, expecting continuous high performance that our biology simply cannot sustain.

The Descent Into the Valley: What Happens After the Peak

As you progress beyond the peak of your cycle, subtle changes begin occurring that signal the approaching valley. Your attention starts wandering more frequently despite your best intentions to stay focused. Simple tasks that felt effortless twenty minutes earlier now require noticeably more mental effort. You might catch yourself reading the same sentence repeatedly without comprehending it, or staring at your work without actually processing what you’re seeing. Physical restlessness increases as your body urges you to move, and you may feel sudden cravings for snacks or stimulants. These aren’t signs of personal weakness or lack of discipline but your nervous system’s way of communicating that you’ve depleted the resources available for that particular cycle.

The valley phase serves essential functions despite feeling frustrating when you’re trying to maintain productivity. During these lower-energy periods, your brain shifts into a different operational mode. Rather than focusing intensely on external tasks, your neural networks become more active internally, consolidating memories from the previous peak period, processing emotions, and making unexpected connections between seemingly unrelated information. This is why insights often arrive when you step away from intense work, why creative breakthroughs happen in the shower, and why sleeping on problems genuinely helps solve them. The valley isn’t wasted time but necessary processing time that prepares you for the next peak. Research published in the journal Nature Neuroscience demonstrates that people who honor these rest periods show significantly better learning retention and creative problem-solving than those who push through without breaks.

Individual Variation Within the General Pattern

While ninety minutes represents the average cycle length, your personal rhythm might run slightly shorter or longer. Some people operate on eighty-minute cycles while others extend to one hundred minutes or more. Additionally, the exact shape of your cycle varies throughout the day based on factors like sleep quality, stress levels, nutrition, and your position within your broader circadian rhythm. Your first cycle after waking might feel particularly strong if you’re well-rested, with a pronounced peak and relatively mild valley. As the day progresses and you accumulate cognitive fatigue, the peaks may become less dramatic and the valleys deeper. By evening, you might find that your cycles have shortened or that distinguishing clear peaks and valleys becomes difficult as overall energy declines.

This variation means you can’t simply set a timer for ninety minutes and expect perfect results. Instead, you need to develop sensitivity to your own body’s signals. Think of the ninety-minute framework as a helpful starting point for observation rather than a rigid rule. Over time, through paying attention to when you feel energized versus depleted, you’ll discover your personal pattern. Some days your cycles might run like clockwork; other days they might feel irregular or difficult to perceive. Both experiences are normal and reflect the complex interplay between your ultradian rhythms and the many other factors influencing your state from moment to moment.

Recognizing Your Personal Cycle Markers

Learning to work effectively with your ninety-minute cycle begins with recognizing when you’re in different phases. Your body provides numerous signals about your current state, but you’ve likely learned to ignore these messages in favor of pushing through according to arbitrary schedules or external demands. Rebuilding this awareness requires deliberate attention and a willingness to trust your body’s feedback. Think of it like learning to sense when you’re truly hungry versus eating because it’s a designated meal time. Initially you might feel uncertain, but with practice, the signals become unmistakable.

Physical Signs of Peak and Valley Phases

During peak phases, your body exhibits specific physical characteristics that reflect optimal functioning. Your posture naturally straightens as your nervous system maintains good muscle tone without conscious effort. Your breathing becomes steady and deep without you needing to think about it. You feel physically comfortable in your chair or workspace, not fidgeting or constantly adjusting your position. Your eyes focus easily on your work without strain, and you can maintain visual attention without frequent breaks to look away. Even small movements feel precise and controlled rather than clumsy or effortful. These subtle cues indicate that your body’s resources are adequately supporting cognitive demands.

As you transition into a valley, physical restlessness increases noticeably. You start shifting in your seat, crossing and uncrossing your legs, or feeling an urge to stand and move. Your shoulders may creep up toward your ears as tension accumulates without you realizing it. Yawning becomes more frequent even if you’re not particularly sleepy, as your brain signals its need for a break. You might notice your jaw clenching, your hands forming fists, or other tension patterns emerging unconsciously. Your eyes feel tired or strained, and you blink more often or rub them. These physical signals precede the mental experience of difficulty concentrating, so learning to recognize them early allows you to transition strategically rather than forcing yourself through mounting discomfort.

Mental and Emotional Indicators

Beyond physical sensations, your mental and emotional state provides clear information about where you are in your cycle. During peak phases, work feels almost effortless. You’re not forcing concentration but simply flowing through tasks with natural momentum. Problems that seemed complicated earlier now have obvious solutions. You generate ideas without strain and words flow naturally when writing or speaking. Time seems to compress as you become absorbed in what you’re doing, looking up in surprise to discover thirty or forty minutes have passed in what felt like ten. This state of engaged ease, sometimes called flow, naturally aligns with the peak portion of your ultradian cycle.

The valley phase brings a distinctly different mental texture. Tasks that should be simple suddenly feel complicated or confusing. You read information without actually processing its meaning, as though your eyes move across the page but comprehension stops somewhere between seeing and understanding. You catch yourself daydreaming or thinking about unrelated topics despite trying to maintain focus. Small frustrations trigger disproportionate irritation, and you might feel brief waves of discouragement about your work or abilities. These emotional shifts aren’t character flaws but neurological realities of depleted cognitive resources. Studies from cognitive psychology research show that people make significantly more errors, demonstrate poorer judgment, and report lower satisfaction with their work when operating in valley phases compared to peak phases, even when task difficulty remains constant.

The Two-Week Tracking Exercise

To develop fluency with your personal cycles, commit to two weeks of systematic observation. Set a gentle reminder every thirty minutes during your workday. When it sounds, briefly note your current mental and physical state using a simple scale: focused and energized, moderately engaged, or tired and distracted. After two weeks, review your notes looking for patterns. You’ll likely discover that your high-energy periods cluster around certain times, typically showing a rhythm close to but not exactly ninety minutes. You’ll also notice how factors like sleep quality, meal timing, and stress levels influence your patterns. This self-knowledge becomes invaluable for scheduling your most important work during your most reliable peak periods and protecting those times from interruptions or low-value activities.

Structuring Your Work Around Natural Cycles

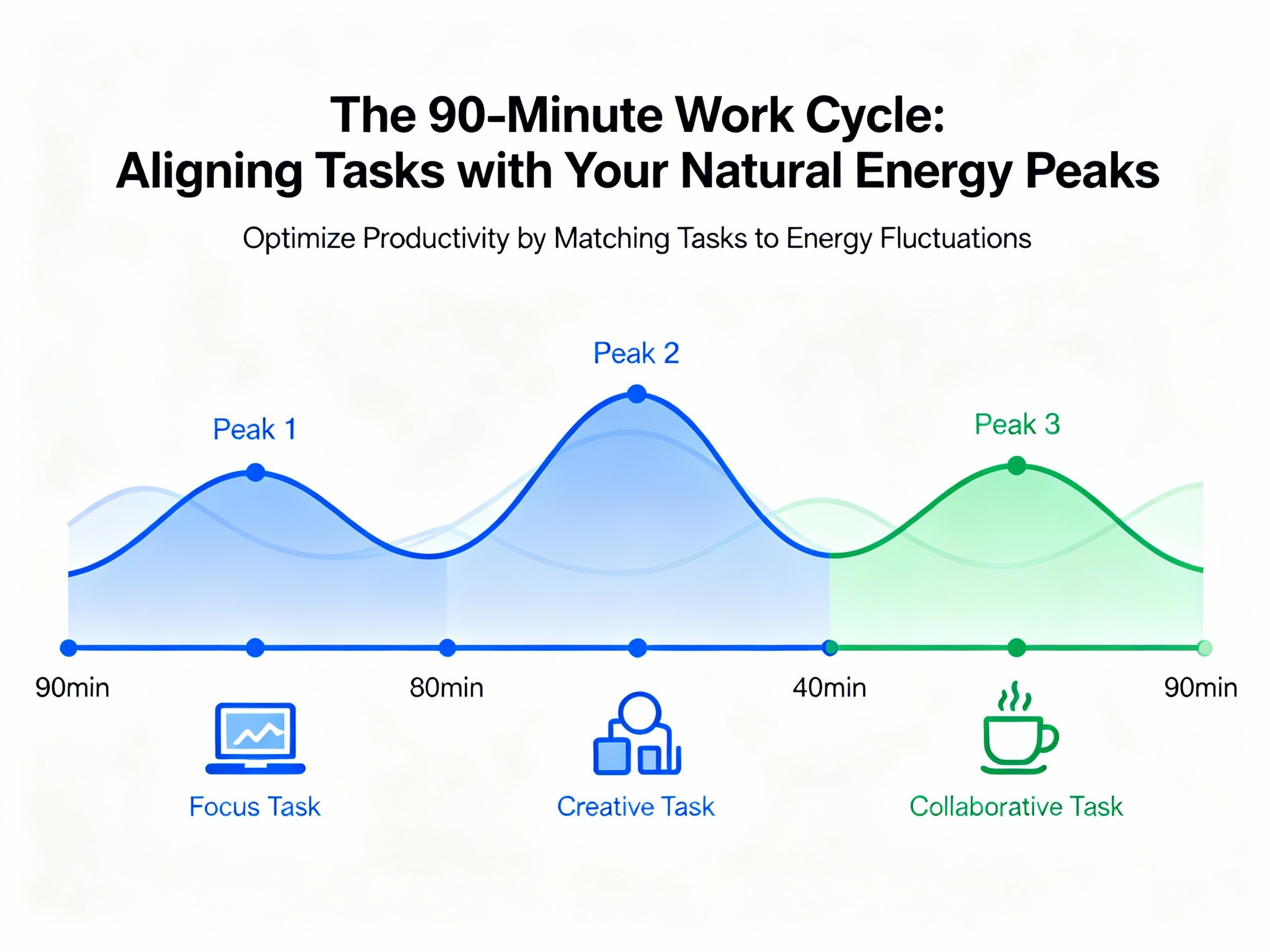

Once you’ve developed awareness of your cycles, the next step involves actively organizing your work to match task demands with your energy availability. This doesn’t mean your entire day must be rigidly scheduled into ninety-minute blocks. Rather, it means becoming strategic about when you tackle different types of work, understanding that your capacity for various activities fluctuates predictably throughout the day. The goal is working with your biology rather than constantly battling against it, which paradoxically allows you to accomplish more while experiencing less strain.

Matching Task Complexity to Cycle Phase

Different types of work make fundamentally different demands on your cognitive systems, which means they’re more or less suitable for different points in your cycle. Deep analytical work that requires sustained concentration and complex reasoning functions best during peak phases when your prefrontal cortex operates at maximum efficiency. This includes activities like writing important documents, solving difficult technical problems, learning new concepts, making significant decisions, or engaging in strategic planning. These tasks consume substantial cognitive resources and produce dramatically better results when you have those resources abundantly available rather than attempting them when depleted.

Conversely, routine tasks that have become largely automatic through repetition can be effectively handled during valley phases. Responding to straightforward emails, organizing files, updating schedules, or performing administrative duties don’t require peak cognitive capacity. In fact, attempting these simpler tasks during your peak phases represents an inefficient use of your most valuable mental resources. Think of it like using a sports car to run errands around your neighborhood when a bicycle would work perfectly well, saving the car for when you genuinely need its performance. By reserving peaks for demanding work and valleys for routine maintenance, you maximize the value extracted from each phase of your cycle.

The Art of the Strategic Break

Taking breaks represents one of the most misunderstood aspects of productive work. Many people view breaks as something you take when you’re being lazy or indulgent, earning them only after extended periods of continuous effort. This mindset fights against your biology and ultimately reduces both productivity and well-being. Your cycles include valley phases not as punishment but as essential recovery periods that restore your capacity for subsequent peaks. Attempting to work through valleys without recovery doesn’t eliminate the valley, it just extends it, creating a prolonged period of low-quality, error-prone work accompanied by mounting frustration and fatigue.

Effective breaks have several important characteristics that distinguish them from mere time-wasting. First, they involve genuine disengagement from work-related thinking. Checking email or thinking about problems doesn’t provide real recovery because your brain remains in work mode even though you’ve stopped actively producing. Second, effective breaks incorporate physical movement whenever possible. Your body wasn’t designed for the prolonged stillness that modern knowledge work demands, and movement helps clear metabolic waste products that accumulate in your brain during intense cognitive effort. Third, breaks should occur proactively based on your cycle timing rather than waiting until you’re completely exhausted. Research from workplace productivity studies consistently shows that people who take regular breaks every ninety minutes maintain higher performance throughout the day compared to those who push through without rest.

The First Cycle of the Day: Making It Count

Your first ultradian cycle after waking typically represents your strongest peak of the entire day, assuming you’re well-rested. During this window, your prefrontal cortex has been restored by sleep, your glucose levels are adequate, and you haven’t yet accumulated the cognitive fatigue that builds throughout waking hours. This makes your first cycle extraordinarily valuable for tackling your most important, most challenging, or most creative work. Yet many people squander this golden period on low-value activities like checking email, scrolling through social media, or reading news. These tasks consume your peak capacity while providing minimal return on that investment.

Protecting your first cycle requires both practical strategies and mindset shifts. Practically, this means delaying your engagement with reactive tasks until after you’ve invested your prime energy in proactive work that moves your most important goals forward. If you typically start work at nine in the morning, your first cycle extends roughly until ten thirty. During this window, close email, silence notifications, and focus exclusively on whatever work matters most to your long-term success. The reactive demands of email and messages will still be there at ten thirty, but you’ll have completed significant work on your priorities when your brain was best equipped for that work. The mindset shift involves recognizing that not all time is equal. Two hours of peak-cycle work often produces more value than six hours of tired, distracted effort later in the day.

Why Mornings Feel Different for Different People

If you’re a natural night owl rather than a morning person, your first cycle after waking might not occur at the traditional morning time, and it might not feel as strong as it does for morning types. This reflects the interaction between your ultradian rhythms and your chronotype, which determines when your circadian alertness peaks. Night owls forced into early schedules might experience their best ultradian cycles during late morning or early afternoon rather than immediately upon waking. The principle remains the same regardless of timing: identify when your strongest cycle occurs and protect that time for your most demanding work. The specific hours matter less than recognizing and honoring your personal pattern rather than forcing yourself into a schedule designed for a different biology.

Common Obstacles and How to Navigate Them

Even when you understand the ninety-minute cycle and want to work with it, practical obstacles often make implementation challenging. Modern work environments weren’t designed with ultradian rhythms in mind, and many organizational practices actively fight against natural cycles. Additionally, individual habits and beliefs about productivity can interfere with adopting cycle-based work patterns. Recognizing these obstacles and developing strategies to navigate them makes the difference between understanding the concept intellectually and actually benefiting from it practically.

Dealing with External Interruptions and Meeting Culture

Meetings represent one of the most significant disruptors of natural work cycles, particularly when scheduled with no regard for how human attention actually functions. A meeting placed forty-five minutes into your peak phase interrupts your momentum just as you’ve hit your stride, forcing you to shift mental gears when you’re optimally configured for deep work. Upon returning from the meeting, you’ve lost the remainder of that peak and must wait for your next cycle to regain similar capacity. Even more problematic are back-to-back meetings that span multiple hours, preventing you from experiencing any complete cycles during those periods.

If you have any control over your schedule, advocate for meeting-free blocks that allow complete cycles to unfold. This might mean proposing that your team designate certain mornings or afternoons as no-meeting times when everyone can engage in focused work. When you must attend meetings during peak times, try to position them near cycle boundaries rather than in the middle of peaks. For instance, scheduling a meeting to begin seventy-five minutes after you start work allows you to complete most of your first cycle before the interruption. Similarly, when you lead meetings, consider timing them for sixty or ninety minutes to align with natural attention spans rather than arbitrary clock times like one hour.

Overcoming the Guilt of Taking Breaks

Many people struggle with taking regular breaks because of deeply ingrained beliefs that equate constant busyness with productivity and value. You might worry that colleagues will perceive you as lazy if they see you taking a walk every ninety minutes, or feel guilty for stepping away when so much work remains undone. These feelings reflect cultural conditioning rather than productivity reality. Ironically, the person who takes strategic breaks every ninety minutes typically accomplishes more high-quality work than the person who sits at their desk for eight hours straight, precisely because the break-taker maintains higher cognitive capacity throughout the day while the continuous worker gradually depletes into ineffectiveness.

Reframing breaks from indulgence to investment helps overcome this guilt. You’re not taking breaks from work but rather investing in your capacity for work. An athlete who trained intensely without any recovery would quickly become injured and unable to perform at all. Your brain requires similar recovery patterns, just on a shorter timescale. When you explain cycle-based work to skeptical colleagues or supervisors, focus on outcomes rather than the methods. Track your productivity during a period of cycle-based work and compare it to your typical output. Most people find that honoring their cycles leads to completing more projects, producing higher-quality results, and experiencing less end-of-day exhaustion, arguments that persuade even productivity-obsessed managers.

When Your Work Truly Cannot Be Interrupted

Some professions genuinely require sustained attention beyond ninety-minute windows. Surgeons performing complex operations, pilots flying aircraft, or emergency responders managing crises cannot simply take breaks when their cycles dictate. However, even in these demanding fields, professionals don’t actually maintain peak performance continuously but rather develop strategies for managing attention within extended periods of required focus. They may use brief mental micro-breaks even while maintaining task engagement, shifting between more and less demanding aspects of their work to provide internal variation that partially mimics cycle benefits.

For most knowledge workers, however, the belief that work cannot be interrupted often reflects habit and fear rather than genuine constraints. You can almost always step away for ten minutes without catastrophic consequences, even if it feels uncomfortable initially. The key question isn’t whether you can physically take breaks but whether the cost of not taking breaks, paid in reduced quality, increased errors, and mounting fatigue, exceeds the temporary discomfort of implementing a new pattern. When you honestly assess this equation, cycle-based work usually emerges as clearly superior despite feeling unfamiliar at first.

Advanced Applications: Going Deeper with Cycle-Based Work

Once you’ve established basic competency with recognizing and honoring your ninety-minute cycles, you can refine your approach to extract even greater benefits. These advanced applications involve more nuanced understanding of how different activities interact with your cycles and how to design your entire workday around natural rhythms rather than arbitrary schedules. While the fundamentals provide substantial improvement, these refinements can elevate your productivity and well-being even further.

Cycling Different Types of Cognitive Work

Not all demanding work makes identical cognitive demands. Some tasks require intense analytical thinking while others need creative imagination. Some involve verbal processing while others engage spatial or mathematical reasoning. Your brain contains different neural networks specialized for different types of cognition, and these networks fatigue at different rates. This means you can sometimes maintain productivity beyond a single ninety-minute cycle by switching between different types of demanding work rather than taking a complete break. After ninety minutes of analytical writing, for instance, you might shift to design work or strategic visualization rather than immediately resting.

This approach requires careful attention to avoid simply pushing through fatigue with a different flavor of work rather than genuinely alternating cognitive demands. The key indicator is whether the new task feels relatively fresh and engaging or whether it feels like a continuation of your depleted state. If switching to a different type of work provides a sense of renewed energy and interest, you’re successfully cycling cognitive demands. If the new task feels just as draining as what you left, you’ve reached genuine depletion and need rest rather than task-switching. Over time, you’ll develop intuition for when alternating work types extends your effective cycle and when you genuinely need to step away completely.

The Two-Cycle Deep Work Block

For particularly important projects requiring sustained immersion, you can structure your day around completing two full ninety-minute cycles with a substantive break between them. This creates a powerful block of deep work totaling about three and a half to four hours including the break, during which you can make extraordinary progress on complex challenges. The pattern works like this: engage in intense focus for your first cycle of roughly ninety minutes, take a genuine twenty-minute break involving movement and mental disengagement, then return for a second ninety-minute cycle of continued deep work on the same project or related tasks.

This two-cycle block feels qualitatively different from simply working for three hours straight. The break between cycles provides enough recovery that your second cycle maintains surprisingly high quality rather than representing a slow deterioration from your first cycle’s peak. You enter your second cycle with renewed energy while maintaining the context and momentum from your first cycle, creating a powerful combination of freshness and continuity. Many knowledge workers find that completing one two-cycle deep work block per day, typically scheduled during their strongest period like early morning, produces more valuable output than an entire day of fragmented attention. Research from productivity science, documented by organizations like the Harvard Business Review, consistently demonstrates that this pattern of intensive work followed by complete recovery outperforms marathon work sessions that attempt to sustain focus for many hours without meaningful breaks.

Aligning Your Daily Schedule with Multiple Cycles

When you have control over your schedule, you can design your entire workday around your natural cycles rather than treating them as isolated phenomena. A well-structured cycle-based day might look like this: you begin with a morning ritual that gently awakens your system without immediately diving into demands, then engage your first peak cycle on your most important work. After a break, you tackle a second demanding project during your second cycle. Your midday break comes during what would likely be a natural energy dip anyway, providing extended recovery. The afternoon includes one or possibly two more cycles, though these later cycles might be reserved for less demanding work as your overall energy declines throughout the day. Evening becomes time for recovery and preparation for the next day rather than attempting to extract additional productivity from a depleted system.

This structure creates a sustainable rhythm that maintains high performance without burning you out. Instead of oscillating between periods of unsustainable intensity followed by collapse, you establish a pattern that you can maintain indefinitely. The psychological benefits prove equally valuable as the productivity gains. When you work with your cycles, you experience your work as challenging but manageable rather than as a constant struggle against your own limitations. You end days feeling accomplished but not destroyed, with energy remaining for personal relationships, hobbies, and life beyond work.

The Weekly Rhythm: Beyond Daily Cycles

Just as your day contains multiple ultradian cycles, your week contains its own rhythm that interacts with daily patterns. Most people find that certain days feel naturally more energetic while others feel more sluggish, even when external circumstances remain similar. This weekly variation might reflect accumulated fatigue, hormonal fluctuations, or other biological factors operating on longer timescales. When planning your week, consider positioning your most demanding projects on days when you typically feel strongest while scheduling lighter work, meetings, or catch-up time on days that tend to feel lower-energy. This macro-level scheduling compounds the benefits of honoring your daily cycles, creating a sustainable work rhythm across multiple timescales simultaneously.

Lifestyle Factors That Support or Undermine Your Cycles

Your ultradian rhythms don’t operate in isolation but interact with numerous lifestyle factors that either enhance or diminish their beneficial effects. Sleep quality, nutrition, physical activity, stress levels, and even your relationships all influence how clearly you experience cycles and how much capacity each peak provides. While you can’t control every variable in your life, understanding these interactions allows you to make choices that support rather than sabotage your natural rhythms.

Sleep: The Foundation of Strong Cycles

The quality of your sleep directly determines the amplitude of your next day’s ultradian cycles. When you sleep well, your peaks feel notably higher and your valleys less severe compared to days following poor sleep. This connection exists because sleep and waking ultradian rhythms share common underlying mechanisms in your nervous system. During sleep, your ninety-minute cycles govern movement through different sleep stages, and the quality of these nocturnal cycles influences your daytime patterns. Fragmented, insufficient, or poorly-timed sleep disrupts this foundation, making your waking cycles feel irregular, weak, or difficult to distinguish.

Prioritizing sleep consistency proves particularly important. Your circadian system, which coordinates your ultradian rhythms, relies on regular timing to function optimally. Going to bed and waking at consistent times, even on weekends, strengthens your rhythm architecture. This doesn’t mean you must be rigidly obsessive about sleep timing, but it does mean that dramatically variable sleep schedules undermine the very patterns you’re trying to work with during waking hours. Studies from sleep research consistently show that people with regular sleep patterns report stronger, more predictable energy cycles during the day compared to those with chaotic sleep schedules.

Caffeine, Food, and Chemical Influences

Caffeine represents both a useful tool and a potential problem for cycle-based work. Strategically timed caffeine can enhance a peak by increasing alertness and focus when consumed early in your cycle. However, using caffeine to override valleys creates problems because it doesn’t actually restore your depleted resources but merely masks the depletion signals. You might feel more alert but your underlying capacity remains compromised, leading to poor quality work despite the sensation of being caffeinated awake. Additionally, caffeine consumed too close to sleep time interferes with sleep quality, undermining tomorrow’s cycles to extend today’s artificially.

Food timing and composition also matter significantly. Large meals trigger digestive processes that compete with cognitive function for your body’s resources, which is why many people feel sluggish after lunch regardless of their cycle timing. Eating lighter, more frequent meals or timing larger meals to coincide with planned breaks helps avoid this conflict. Similarly, dramatic blood sugar swings from high-sugar foods can create artificial energy fluctuations that obscure your natural cycles. Stable blood sugar through balanced nutrition allows your authentic rhythms to emerge more clearly, making them easier to recognize and work with effectively.

Movement, Exercise, and Physical State

Regular physical movement throughout your day supports stronger ultradian cycles through multiple mechanisms. Exercise increases blood flow to your brain, delivering oxygen and nutrients while removing metabolic waste products. This enhanced circulation makes your peaks feel sharper and helps you recover more quickly during valleys. Movement also triggers release of neurochemicals like brain-derived neurotrophic factor that support neural health and cognitive function. Even brief movement breaks between cycles provide these benefits, which is why a ten-minute walk often feels so restorative despite taking you away from your work.

Beyond these direct effects, regular exercise improves sleep quality, which as we discussed earlier, strengthens your cycles indirectly. The timing of exercise matters somewhat, with morning or midday activity generally supporting better daytime energy patterns than evening exercise, which can interfere with sleep for some people. However, any exercise proves better than none, so the best timing is whatever fits your schedule and you’ll actually maintain consistently. The goal isn’t athletic performance but supporting your cognitive rhythms through basic physical maintenance.

Your Personal Implementation Plan

Knowledge about ultradian cycles becomes valuable only when you translate it into consistent practice. The gap between understanding and implementation trips up many people who intellectually grasp these concepts but struggle to make them habits. Closing this gap requires a structured approach that builds gradually rather than attempting overnight transformation.

Begin with awareness before attempting change. For at least one week, simply observe your energy patterns without trying to modify them. Notice when focus comes easily versus when it requires force. Track when breaks feel necessary and how you feel after taking them versus pushing through. This observation period builds your sensitivity to your cycles and provides baseline data about your current patterns.

After your observation week, implement one change at a time rather than overhauling everything simultaneously. Perhaps you start by protecting your first ninety-minute cycle each morning for important work rather than email. Once that habit feels established after a few weeks, add strategic breaks every ninety minutes. Then work on matching task types to cycle phases. This gradual approach prevents overwhelm and allows each change to become automatic before adding new complexity.

Expect imperfect implementation. Some days, external demands will override your ideal cycle-based schedule. Meetings will interrupt peaks, deadlines will force work during valleys, and life will generally refuse to conform perfectly to your plans. This variability is normal and doesn’t represent failure. The goal isn’t perfect adherence but rather working with your cycles when possible and recognizing when you’re fighting against them so you can adjust your expectations and strategies accordingly.

Finally, remain flexible and experimental in your approach. Your cycles might not match the average ninety-minute pattern exactly, or they might vary based on factors you haven’t yet identified. Stay curious about your personal patterns rather than trying to force yourself into a predetermined mold. Over months and years, you’ll develop increasingly sophisticated understanding of how your particular nervous system operates, allowing you to craft a work style that feels sustainable, productive, and aligned with your natural rhythms rather than constantly fighting against them.

“Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished.” — Lao Tzu. Your brain’s natural ninety-minute rhythm embodies this principle, showing that working with your biology’s timing rather than against it allows both rest and productivity to coexist in sustainable patterns.

Resources for Continued Learning

For readers interested in exploring the science of ultradian rhythms and their applications more deeply, these authoritative resources provide research-based information and practical guidance:

- Sleep Foundation – Comprehensive information on sleep cycles and their relationship to waking performance patterns

- National Center for Biotechnology Information – Peer-reviewed research on ultradian rhythms and cognitive performance

- American Psychological Association – Studies on attention, fatigue, and optimal work patterns

- Harvard Business Review – Practical applications of rhythm-based work to organizational productivity

- Nature Neuroscience – Advanced research on brain rhythms and their behavioral manifestations

The journey toward working with your ninety-minute cycles represents a shift from fighting your biology to collaborating with it. This partnership between your conscious intentions and your nervous system’s natural patterns creates space for both peak performance and genuine recovery, allowing you to accomplish meaningful work while maintaining the energy and well-being to enjoy life beyond your productivity. As you develop fluency with your cycles over coming weeks and months, you’ll likely find that this approach feels less like a productivity technique and more like finally understanding how you were designed to function all along.