Your brain doesn’t operate at a constant level throughout the day. Instead, it follows predictable patterns of peaks and valleys in cognitive performance, governed by complex biological rhythms that evolved over millions of years. Understanding these patterns represents one of the most powerful yet underutilized strategies for improving your productivity. When you align your work tasks with your brain’s natural cycles, you can accomplish more while expending less mental energy and experiencing significantly less frustration.

Think of your cognitive capacity like a tide that rises and falls throughout the day. Just as a skilled sailor works with the tides rather than against them, effective knowledge workers learn to schedule demanding tasks during their mental high tides and reserve less demanding work for the ebbs. This isn’t about working harder but about working smarter by respecting your biology. The science behind these patterns is well-established, yet most people continue organizing their days based on external schedules rather than internal readiness.

Understanding Your Circadian Rhythm and Cognitive Performance

Before exploring optimal timing for specific tasks, you need to understand the biological foundation that governs your daily cognitive fluctuations. Your circadian rhythm is an internal 24-hour clock that regulates numerous physiological processes, including body temperature, hormone release, and crucially for our purposes, mental alertness and cognitive capacity. This isn’t merely about feeling tired or awake but involves measurable changes in brain chemistry and neural efficiency.

The circadian system originates in a cluster of neurons in your hypothalamus called the suprachiasmatic nucleus. This tiny brain structure, containing only about twenty thousand neurons, acts as your master clock. It receives direct input from your eyes about environmental light levels and uses this information to coordinate the timing of virtually every system in your body. Research published in the journal Nature has demonstrated that cognitive abilities like attention, working memory, and processing speed all follow circadian patterns with predictable peaks and troughs.

Why Body Temperature Matters for Mental Performance

Your core body temperature follows a daily rhythm, typically reaching its lowest point around four to five in the morning and peaking in the late afternoon or early evening. This temperature variation isn’t random but directly correlates with cognitive performance. As your body temperature rises throughout the morning, so does your alertness and processing speed. This explains why most people find analytical tasks easier as the day progresses, even though they may feel subjectively more tired. Understanding this connection helps you predict when different cognitive abilities will be at their strongest.

Chronotypes: The Morning Person and Night Owl Spectrum

While circadian rhythms are universal, individuals vary significantly in when their peak performance occurs. This variation, called your chronotype, represents your biological preference for earlier or later activity. Think of chronotypes as existing on a spectrum. At one end are extreme morning types who wake naturally at dawn, reach peak alertness within hours, and feel sleepy by early evening. At the other extreme are night owls who struggle with early mornings, hit their stride in the afternoon or evening, and naturally stay alert into the late hours.

Most people fall somewhere in the middle, with a slight tendency toward one direction or the other. Your chronotype is largely genetic, determined before birth, and relatively stable throughout your adult life. This means fighting against your chronotype by forcing yourself to work during your biological low periods is like swimming against a strong current. You can do it, but it requires significantly more energy and yields poorer results than working with your natural rhythm. Studies from the Sleep Foundation show that people who align their schedules with their chronotype report higher life satisfaction and better health outcomes.

The Ultradian Rhythm Within Your Day

Beyond the broad circadian pattern, your brain also operates on shorter cycles called ultradian rhythms. These ninety-minute cycles govern your capacity for sustained focus and attention. During the first part of each cycle, your ability to concentrate is high and you can maintain deep focus. As you approach the end of the cycle, your attention naturally wanes and you experience increasing mental fatigue and distractibility.

This pattern mirrors your sleep cycles and reflects fundamental aspects of brain function. Your brain cannot sustain maximum performance indefinitely but needs periodic recovery. Effective productivity strategies honor these ultradian rhythms by structuring work in aligned blocks with recovery periods between them. When you push through the natural lull at the end of an ultradian cycle, forcing continued focus, you deplete mental resources more rapidly and produce lower quality work. Conversely, taking a brief break when your brain signals the end of a cycle allows resources to replenish, enabling another high-quality focus period.

Morning Hours: Peak Time for Analytical and Strategic Thinking

For most people, the hours between waking and early afternoon represent the day’s cognitive peak. During this window, your prefrontal cortex operates at maximum efficiency. This brain region, located behind your forehead, handles what neuroscientists call executive functions: planning, reasoning, problem-solving, and inhibiting inappropriate responses. These are precisely the capacities you need for deep analytical work, strategic planning, and complex problem-solving.

Think about what happens when you try to solve a difficult problem late in the evening versus first thing in the morning. In the morning, solutions often seem clearer, you can hold more variables in your working memory simultaneously, and logical connections appear more readily. This isn’t just about feeling more rested but reflects actual changes in how efficiently your neural networks operate. Your prefrontal cortex has fresh supplies of glucose and neurotransmitters, and the previous night’s sleep has cleared metabolic waste products that accumulate during waking hours.

The First Two Hours After Waking: Your Golden Window

The period immediately following your wake time deserves special attention. During this window, your cortisol levels naturally peak, providing alertness and energy. Simultaneously, your prefrontal cortex has been restored by sleep and operates with maximum efficiency. This combination creates what productivity researchers call your biological prime time for demanding cognitive work. However, many people squander this golden window on low-value activities like checking email or social media, reserving deep work for later when their mental capacity has already diminished.

Consider protecting this window zealously for your most important and challenging work. If you’re writing a difficult proposal, solving a complex problem, or making a significant strategic decision, scheduling it during your first two hours awake maximizes your chances of producing exceptional results. Research from cognitive psychology studies consistently shows that complex problem-solving performance declines throughout the day, with morning performance significantly superior to afternoon attempts at the same tasks.

Late Morning: Sustained Focus and Detail Work

As you move into late morning, typically between ten and noon for most people, your cognitive profile shifts slightly. While raw analytical power may have peaked earlier, your ability to sustain attention reaches its daily high. Your body temperature continues rising, supporting alertness, and you’ve fully transitioned from any residual sleep inertia that sometimes lingers in the very early morning. This makes late morning ideal for work requiring sustained, focused attention to detail.

Tasks like editing documents, reviewing contracts, conducting detailed quality assurance, or working through systematic processes fit beautifully into this window. You’re alert enough to catch small errors and focused enough to maintain concentration through potentially tedious work. The key distinction from early morning is that late morning favors execution and refinement over initial creation or high-level strategy. You’re implementing the plans and solving the problems you identified earlier rather than generating entirely new approaches.

Morning Routines That Enhance Cognitive Performance

How you spend the first hour after waking significantly influences your entire day’s cognitive performance. Exposure to bright light, particularly natural sunlight, helps reset your circadian clock and promotes alertness. Light physical movement increases blood flow to the brain and enhances mood-regulating neurotransmitters. Brief mental exercises like journaling or meditation activate your prefrontal cortex without depleting it. Conversely, immediately diving into email or consuming distressing news can trigger stress responses that impair the very cognitive capacities you need for demanding work. Design your morning routine to prepare your brain for peak performance rather than overwhelming it before your important work begins.

Midday: Strategic Break Time and Transitional Tasks

The midday period presents interesting challenges and opportunities for knowledge workers. Most people experience a dip in alertness and cognitive performance during early afternoon, typically between one and three in the afternoon. This post-lunch slump isn’t primarily about what you ate for lunch, though heavy meals can exacerbate it. Instead, this trough reflects a natural dip in your circadian rhythm, a biological reality that affects virtually everyone regardless of meal timing or composition.

Understanding this inevitable decline allows you to work with it rather than fighting against it. Trying to force deep analytical work during your biological low point is inefficient and frustrating. Your prefrontal cortex operates at reduced capacity, making complex reasoning more difficult. Working memory holds fewer items simultaneously. Attention wanders more easily. These aren’t failures of willpower but natural fluctuations in neural efficiency that everyone experiences.

Leveraging the Midday Dip Strategically

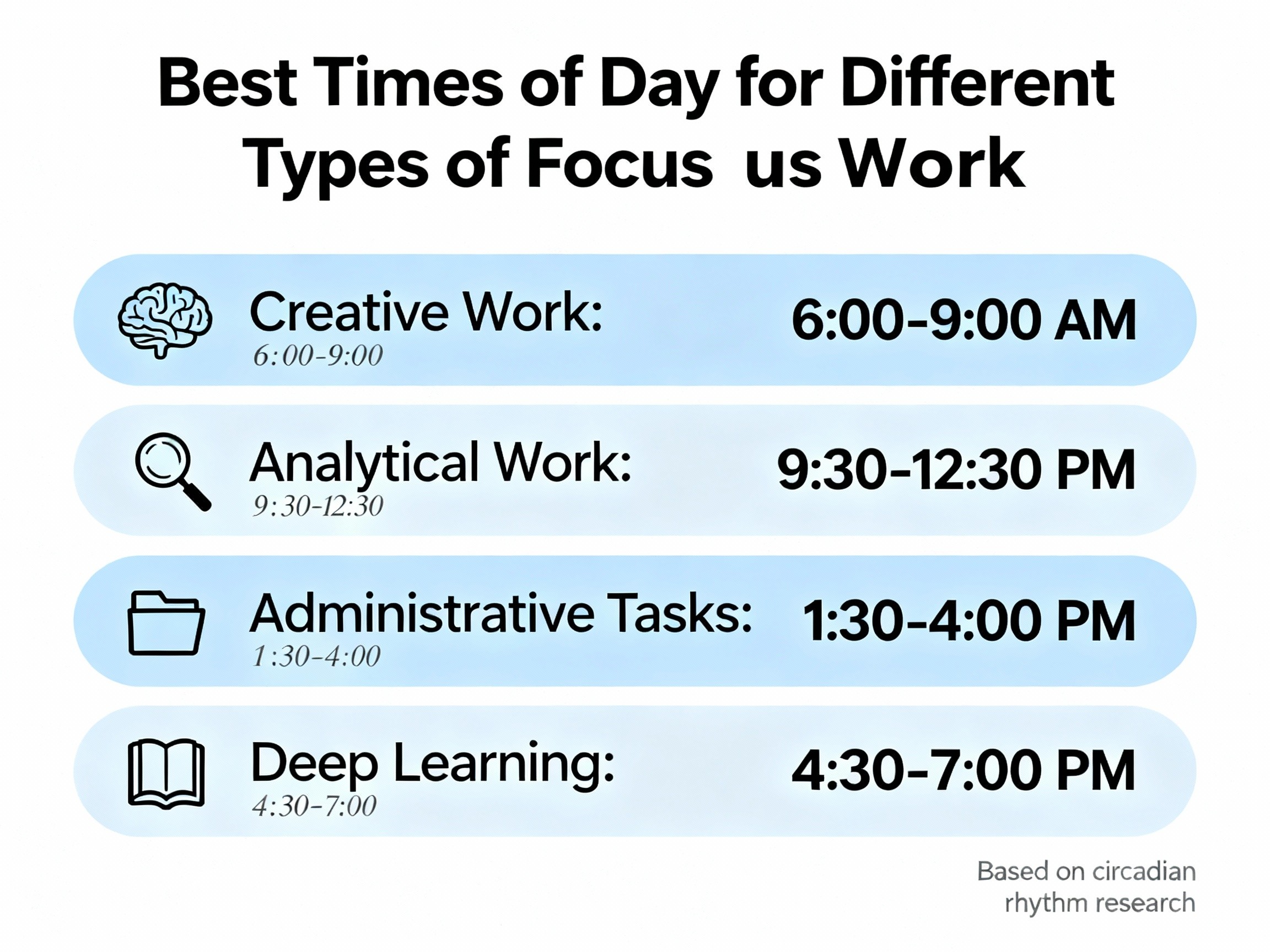

Rather than viewing the afternoon slump as wasted time, you can strategically schedule activities that don’t require peak cognitive capacity. Administrative tasks like responding to routine emails, organizing files, scheduling meetings, or updating systems become appropriate midday activities. These tasks need to be completed but don’t benefit significantly from your highest levels of mental clarity. By clustering them during your natural energy trough, you free your peak hours for work that truly requires them.

This is also an excellent time for collaborative work and meetings that don’t require intense individual focus. Social interaction can provide a mild boost to alertness during your biological low point. Brainstorming sessions, team check-ins, or informal discussions can feel more energizing than solitary focus work during this period. Research from organizational behavior studies shows that scheduling collaborative activities during the post-lunch period often yields better engagement than morning slots when people might prefer to work independently during their peak cognitive hours.

The Power of the Midday Break

Perhaps the most powerful use of the midday dip is taking an actual break. Many cultures traditionally incorporate afternoon rest periods, and neuroscience supports this wisdom. A brief nap of fifteen to twenty minutes can significantly restore alertness and cognitive performance without causing the grogginess associated with longer naps. During this brief sleep, your brain clears adenosine, a fatigue-inducing neurotransmitter that accumulates during waking hours, partially resetting your alertness levels.

Even if napping isn’t feasible in your work environment, other restoration strategies can help. A walk outside exposes you to natural light and movement, both of which counteract the afternoon dip. Stepping away from work for genuine mental rest, rather than switching to another demanding task, allows recovery. Studies from sleep research demonstrate that people who take strategic afternoon breaks perform better on subsequent cognitive tasks than those who push through without rest, even when total working time is equal.

Late Afternoon and Evening: Creative Problem-Solving and Insight Generation

As afternoon transitions to evening, your cognitive profile undergoes another fascinating shift. While your capacity for focused, analytical thinking may have declined from its morning peak, different cognitive strengths emerge. Your brain becomes less rigidly focused and more capable of making unexpected connections, a state neuroscientists associate with creative insight. The slightly tired, less inhibited brain of late afternoon is actually better equipped for certain types of creative problem-solving than the sharply focused morning brain.

This phenomenon relates to how your prefrontal cortex functions. In the morning, this region tightly controls your attention, filtering out irrelevant information and maintaining focus on your chosen task. This focus is invaluable for analytical work but can actually hinder creativity. Creative breakthroughs often require making connections between seemingly unrelated concepts, which means you need your mental filters to be slightly more relaxed. As your prefrontal cortex tires in the afternoon, it exerts less stringent control, allowing your mind to wander more freely and consider unconventional associations.

The Creative Advantage of Mental Fatigue

Research published in the journal Thinking & Reasoning demonstrates that people often perform better on insight problems during their non-optimal times of day. Morning people solve creative problems more successfully in the evening, while night owls excel at creative tasks in the morning. This counterintuitive finding reflects the benefits of reduced cognitive control for certain types of thinking. When your inhibitory mechanisms are slightly weakened by fatigue, you’re more likely to consider unusual solutions that your well-rested, focused brain would dismiss as irrelevant.

Late afternoon becomes an excellent time for brainstorming, exploring new approaches to persistent problems, or engaging in free-form creative work. Writing that prioritizes expression over precision, artistic activities, or strategic thinking about long-term possibilities can flourish during this period. You’re not trying to execute detailed plans but rather generating ideas and possibilities that you can later evaluate and refine during your analytical peak hours.

Secondary Cognitive Peak in Early Evening

Many people experience a secondary surge in alertness during early evening, typically between five and seven in the evening. Your body temperature reaches its daily peak during this window, and various cognitive abilities show measurable improvement compared to the afternoon trough. This evening peak isn’t as pronounced as your morning optimum for most people, but it represents a genuine opportunity for productive work, particularly for tasks requiring moderate focus and execution rather than deep analytical thinking.

Evening hours work well for tasks that benefit from the day’s accumulated knowledge and context. If you’ve been working on a project throughout the day, the evening can be an excellent time to synthesize your findings, draw conclusions, or prepare presentations. You have all the day’s information fresh in your mind, and your moderate alertness supports organizing and communicating this information, even if you wouldn’t want to tackle entirely new analytical challenges during this period.

Night Owls: A Different Rhythm Entirely

If you’re a genuine night owl, your entire cognitive rhythm operates on a delayed schedule compared to average chronotypes. Your peak analytical hours might not arrive until late morning or early afternoon, and your creative sweet spot could extend deep into the evening or even early morning hours. The principles discussed here still apply to you, but shifted several hours later. The key is identifying your personal pattern rather than forcing yourself into a schedule designed for morning-type individuals. When night owls are allowed to work during their optimal hours, their performance equals or exceeds morning types, but forcing them into early schedules significantly impairs their cognitive function and well-being.

Designing Your Personalized Daily Cognitive Schedule

Understanding general patterns is valuable, but maximizing your productivity requires identifying your personal cognitive rhythm. Individual variation means that generic advice won’t serve everyone equally. Some people genuinely do their best analytical work in the evening, while others hit their creative peak in the early morning. The goal is discovering your unique pattern through systematic observation and experimentation.

The Two-Week Attention Audit

Begin by tracking your energy and focus levels for two weeks. Set reminders to rate your alertness, ability to concentrate, and mood at consistent intervals throughout each day. Note what type of work you’re doing, whether you feel the task is easy or difficult, and how satisfied you are with your output. This data collection requires minimal time but provides invaluable insights into your personal patterns.

After two weeks, analyze the data for patterns. When do you consistently report high energy and focus? When does concentration feel difficult regardless of the task? Are there unexpected times when you feel surprisingly alert or particularly creative? These patterns reveal your personal cognitive landscape. You might discover, for instance, that while most people experience an afternoon slump around two, yours occurs at three thirty, giving you an extra ninety minutes of productive time that you’d been wasting on administrative tasks.

Creating Your Energy-Task Matrix

Once you understand your energy patterns, create a matrix matching your regular tasks to your optimal times. List all your recurring work activities and categorize them by cognitive demand. Which require intense focus and analytical thinking? Which benefit from creative freedom? Which are relatively mindless but necessary? Then map these categories onto your energy schedule, creating a template for your ideal workday.

This doesn’t mean your schedule will be perfect every day, but having a clear template helps you make better decisions about task sequencing. When you have flexibility, you can choose to tackle your most demanding work during your peak hours. When external constraints force scheduling conflicts, you can at least be strategic about which suboptimal arrangements you accept. Knowing you’re working against your rhythm helps you plan accordingly, perhaps breaking a difficult task into smaller pieces or scheduling extra time because you’re operating at reduced capacity.

Protecting Your Peak Hours

One of the most common productivity mistakes is allowing your peak cognitive hours to be consumed by reactive work and meetings. Your email inbox, which represents other people’s agendas for your time, shouldn’t dictate how you use your most valuable mental resources. Similarly, meetings scheduled during your peak hours often represent an inefficient use of your optimal state, particularly routine check-ins or information-sharing sessions that don’t require your highest cognitive capacity.

Develop strategies to defend your peak hours for your most important work. This might mean blocking calendar time, establishing communication norms with colleagues about when you’re available, or creating systems that batch reactive work during your lower-energy periods. While you can’t control every aspect of your schedule, most knowledge workers have more autonomy than they exercise. Actively protecting even one or two peak hours per day for focused work can dramatically improve your output and job satisfaction.

The Flexibility Principle

While structure helps optimize your daily rhythm, rigid adherence to schedules can create problems. Some days, despite being your normal peak time, you’ll feel unusually tired or distracted. Other days, you might experience unexpected energy during typically low periods. Rather than forcing yourself through a suboptimal state because your schedule says it’s time for deep work, develop flexibility to adjust based on your actual condition. If you feel unusually alert in the afternoon, take advantage of it. If your morning brain feels sluggish, shift to easier tasks and reserve demanding work for when your energy returns. This responsiveness to your actual state rather than theoretical patterns yields better results than rigid scheduling.

Environmental and Lifestyle Factors That Influence Daily Rhythms

Your cognitive rhythm doesn’t operate in isolation but interacts with numerous lifestyle and environmental factors. Understanding these influences allows you to optimize conditions for each phase of your day, amplifying your natural cognitive strengths and partially compensating for inevitable low periods.

Light Exposure and Circadian Alignment

Light is the primary signal your circadian system uses to maintain its twenty-four-hour rhythm. Exposure to bright light, particularly natural sunlight, in the morning helps anchor your circadian clock, promoting alertness throughout the day and better sleep at night. Conversely, bright light exposure in the evening, especially blue-wavelength light from screens, can delay your circadian phase, making it harder to fall asleep and potentially shifting your entire rhythm later.

Strategically managing light exposure can enhance your cognitive performance throughout the day. Getting outdoor light exposure within an hour of waking helps solidify your morning alertness. Working near windows or taking brief outdoor breaks maintains this benefit. In the afternoon, when you might naturally feel sluggish, exposure to bright light can provide a mild alertness boost. As evening approaches, dimming your environment and limiting screen exposure helps maintain your natural circadian timing, ensuring better sleep and subsequently better morning cognitive performance.

Physical Activity and Cognitive Enhancement

Exercise influences cognitive function through multiple mechanisms, and the timing of physical activity can strategically support your cognitive rhythm. Morning exercise, particularly if done outdoors, provides both light exposure and increased blood flow to the brain, enhancing the natural morning alertness surge. However, intense morning workouts can also be depleting if you’re not a natural morning person, potentially impairing rather than enhancing cognitive performance.

For many people, moderate physical activity during the afternoon energy trough provides valuable benefits. A walk, light workout, or even standing and stretching can counteract the natural post-lunch dip. The increased heart rate and body movement provide a temporary alertness boost without the sleep-disrupting effects that afternoon caffeine might cause. Research from Harvard Health demonstrates that brief physical activity breaks improve subsequent cognitive performance, particularly on tasks requiring sustained attention.

Nutrition Timing and Mental Performance

While the post-lunch dip is primarily circadian rather than food-induced, what and when you eat does influence your cognitive capacity. Large meals trigger digestive processes that divert blood flow and can increase sleepiness, particularly during the naturally low afternoon period. Heavy, carbohydrate-rich lunches tend to exacerbate afternoon sluggishness more than lighter, protein-focused meals.

Strategic eating means consuming adequate nutrition to fuel your brain without overwhelming your system during times when you need cognitive performance. Eating a substantial, balanced breakfast supports morning cognitive work by providing necessary glucose and nutrients after the overnight fast. A lighter lunch prevents excessive post-meal drowsiness during the already challenging afternoon period. If you experience late afternoon hunger that impairs focus, a small snack combining protein and complex carbohydrates can stabilize blood sugar without creating the sluggishness of a large meal.

Adapting to Constraints: Making the Best of Imperfect Schedules

While understanding optimal timing is valuable, most people face constraints that prevent perfectly aligning their work with their biological rhythms. Meetings get scheduled during peak hours. Deadlines force work during low-energy periods. Family responsibilities conflict with ideal cognitive timing. Rather than viewing these conflicts as failures, you can develop strategies to partially compensate and minimize the productivity cost of suboptimal scheduling.

Compensation Strategies for Suboptimal Timing

When you must perform demanding cognitive work during your low-energy periods, several strategies can partially offset the disadvantage. Breaking the work into smaller chunks with breaks between them reduces the sustained attention demand that’s particularly difficult during troughs. Increasing environmental stimulation through brighter light, standing rather than sitting, or working in a slightly cooler environment can provide mild alertness boosts. Collaborating with others can make difficult work more engaging during periods when solo focus feels impossible.

Lowering your expectations appropriately also matters. When working during suboptimal times, you’re not operating at full capacity, and accepting this reality reduces frustration. A task that would take thirty minutes during peak hours might require forty-five minutes during a low period. Planning for this additional time prevents the stress of falling behind schedule. Similarly, work produced during low-energy periods might benefit from revision during your next peak period, when you can more easily spot errors or weak reasoning.

Gradual Schedule Shifting

If your work schedule fundamentally misaligns with your chronotype, you might consider whether gradual shifts are possible. Organizations are increasingly recognizing the value of flexible scheduling that allows employees to work during their optimal hours. If you’re a night owl forced into an early schedule, even shifting your start time by one or two hours can significantly improve your cognitive performance and well-being.

When requesting schedule changes, framing the discussion around productivity and output rather than personal preference often yields better results. Demonstrating through tracked metrics that your performance improves during different hours provides compelling evidence. Many managers are receptive to alternative schedules when they understand the performance benefits, particularly for individual contributor roles where coordination with others is less critical than output quality.

Implementing Your Timing Strategy: A Practical Framework

Understanding the science of cognitive timing is valuable, but the real benefit comes from implementation. Here’s a structured approach to aligning your work with your biological rhythms over the next month.

Week One: Observation and Data Collection

Track your energy, focus, and performance at two-hour intervals throughout each day. Note what you’re working on and how difficult it feels. This creates your personal cognitive map without changing your existing habits.

Week Two: Analysis and Planning

Review your data to identify clear patterns in your peak focus times, creative periods, and energy troughs. List your regular work tasks and categorize them by cognitive demand. Create a template schedule matching task types to your optimal times.

Week Three: Gradual Implementation

Begin scheduling one or two high-priority tasks during your identified peak hours each day. Shift routine administrative work to your low-energy periods. Don’t try to overhaul your entire schedule immediately, but make strategic adjustments where you have control.

Week Four: Refinement and Expansion

Evaluate what’s working and what isn’t. Expand successful timing strategies to more of your work. Identify remaining constraints and develop creative solutions or acceptable compromises. Continue tracking to measure improvements in productivity and satisfaction.

Remember that perfect alignment is impossible and unnecessary. Even modest improvements in matching your work to your rhythms can yield significant benefits in productivity, work quality, and how you feel at the end of each day. The goal isn’t perfection but optimization within your real-world constraints, respecting your biology while meeting your responsibilities.

“Time isn’t the main thing. It’s the only thing.” — Miles Davis. Understanding not just how much time you have, but when you have it and what your brain is capable of during those hours, transforms how effectively you work and live.

Deepening Your Understanding: Additional Resources

For those interested in exploring the science of cognitive timing more deeply, these authoritative resources provide research-based insights and practical applications:

- National Sleep Foundation – Comprehensive information on circadian rhythms, chronotypes, and sleep science affecting daily performance

- National Center for Biotechnology Information – Peer-reviewed research on circadian biology and cognitive performance

- American Psychological Association – Studies on attention, working memory, and daily cognitive fluctuations

- Harvard Business Review – Practical applications of timing research to workplace productivity

- Scientific American – Accessible explanations of neuroscience research on daily brain rhythms

The journey to optimal cognitive timing is ongoing rather than a destination. As your life circumstances change, as seasons shift your light exposure, or as you age and your chronotype evolves, your optimal schedule may shift. Maintaining awareness of your cognitive patterns and remaining willing to adjust your approach ensures you continue working with rather than against your biology throughout your career and life.