Let me ask you to think honestly about how many apps currently sit on your phone promising to improve your memory, boost your productivity, or accelerate your learning. Perhaps you have downloaded flashcard apps like Anki or Quizlet, spaced repetition systems, language learning platforms, note-taking applications with sophisticated tagging and search features, or specialized memory training games that claim to exercise your brain through daily practice. Now I want you to consider how many of these apps you actually use consistently versus how many gathered digital dust after the initial enthusiasm wore off within days or weeks of installation. If you are like most people, the ratio is quite sobering. Your phone contains a graveyard of abandoned productivity and learning apps, each representing a moment of optimism followed by gradual neglect as the friction of opening the app, navigating its interface, and maintaining the required routines proved greater than your sustained motivation could overcome.

This pattern of downloading, briefly using, then abandoning learning apps is so common that it has become an accepted part of modern life, but I want to challenge you to consider whether the problem lies not with your discipline but rather with a fundamental mismatch between how these digital tools work and how human memory actually operates. What if I told you that many traditional memory techniques developed centuries or even millennia before smartphones, techniques that require nothing but your own mind and perhaps a piece of paper, often produce better long-term results than the most sophisticated modern apps with their algorithms and notifications and gamification systems? This might sound like romantic nostalgia for a pre-digital past, but the comparison is grounded in solid cognitive science and practical experience. Traditional memory techniques succeed not despite their simplicity but because of it, engaging your brain’s natural learning mechanisms without the cognitive overhead, distraction potential, and dependency issues that plague even well-designed apps. In this article, I want to help you understand why traditional memory methods often outperform modern digital alternatives, teach you several powerful traditional techniques you can start using immediately, and show you how to reclaim cognitive independence that makes you a more capable learner regardless of what technology you have available.

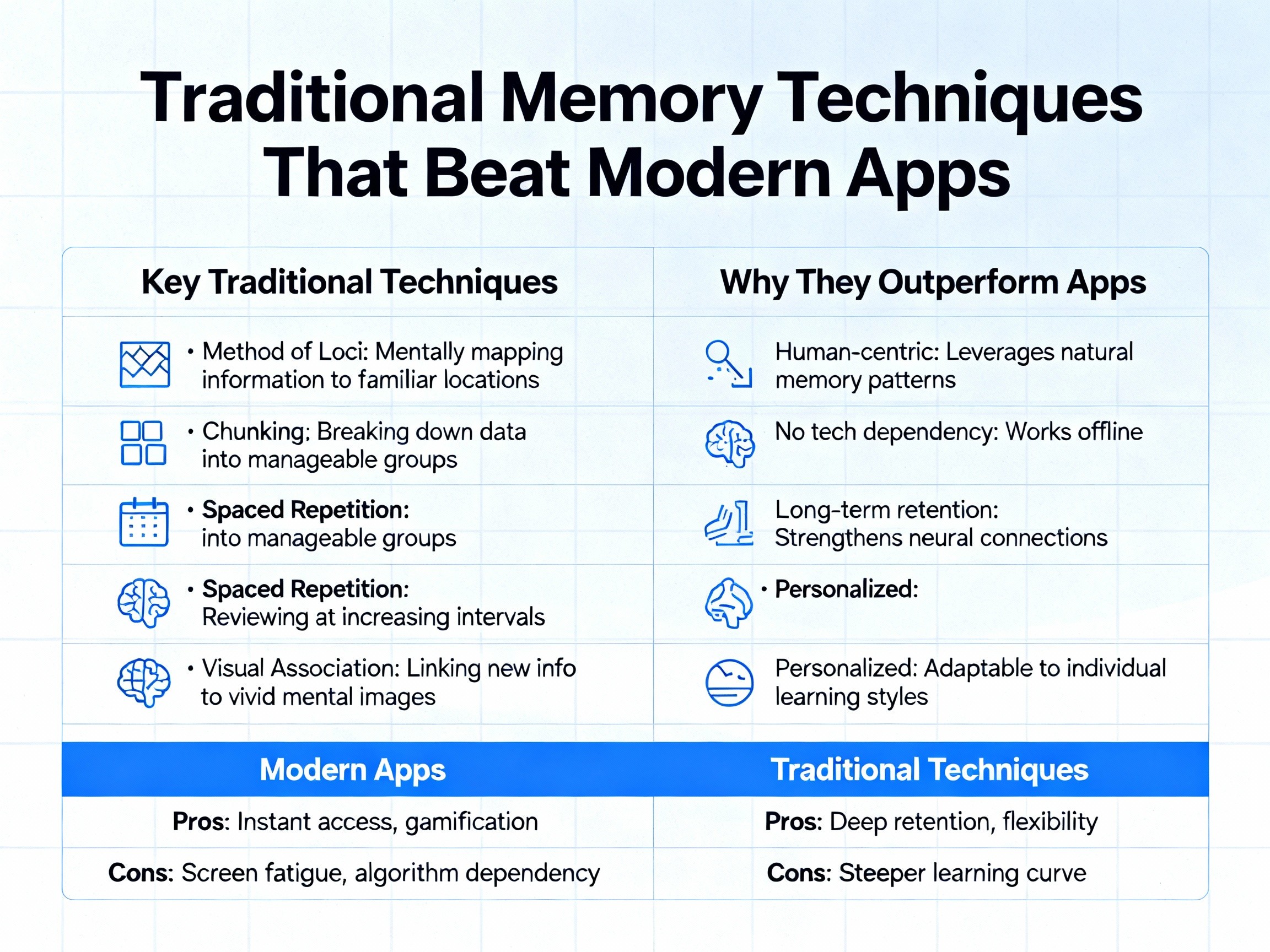

Understanding Why Traditional Techniques Often Outperform Apps

Before I teach you specific traditional memory techniques, you need to understand the fundamental reasons why methods requiring nothing but your mind often produce better outcomes than sophisticated digital tools backed by research and algorithms. This understanding is crucial because without it, you might view traditional techniques as quaint relics worth trying for novelty but ultimately inferior to modern solutions, when the reality is often precisely the opposite. The advantages of traditional memory methods stem from several interconnected factors involving cognitive engagement, accessibility, distraction avoidance, and the development of genuine mental capabilities rather than dependence on external systems.

Let me start by helping you understand what I call the effort paradox in learning technology. Modern apps are designed to make learning feel easy and frictionless, with smooth interfaces, automated scheduling, immediate feedback, and gamification elements that provide constant positive reinforcement. These features seem beneficial and indeed make apps feel pleasant to use in the moment, but they create a subtle problem that undermines long-term learning. When an app makes the learning process too easy and handles too much of the cognitive work for you, your brain engages less deeply with the material because it is not forced to struggle with encoding, organization, or retrieval. Research in cognitive psychology consistently demonstrates that some degree of difficulty during learning, what scientists call desirable difficulty, actually enhances long-term retention even though it feels harder and slower in the moment. When you flip through digital flashcards with a quick swipe, the ease and speed prevent the deep processing that occurs when you must actively work to remember something without external prompts.

Traditional memory techniques, by contrast, require genuine mental effort. When you create a mnemonic device to remember a list, your brain must actively encode the items, create meaningful connections between them, and often generate visual imagery or narrative structure that links everything together. This effortful processing feels harder than scrolling through an app, but it creates much stronger memory traces precisely because your brain had to work to create them. Think of it like the difference between watching someone else solve a math problem versus solving it yourself. Watching feels easier and you might believe you understand, but genuine learning occurs through the struggle of working through the problem independently. Traditional memory techniques force this productive struggle, while many apps inadvertently remove it in the name of user-friendliness, creating an illusion of learning without the deep encoding that produces lasting knowledge. The irony is that the very features that make apps feel effective in the moment, their smoothness and ease, often undermine the cognitive processes that create durable learning.

The Problem of Digital Distraction and Context Switching

One of the most significant but underappreciated disadvantages of app-based learning involves the distraction potential inherent in using any digital device. When you open your phone or computer to use a learning app, you enter an environment saturated with competing demands for attention. Notifications from messaging apps, social media, email, and countless other sources constantly interrupt your focus, and even if you ignore specific notifications, the mere presence of your device creates cognitive burden through what researchers call attention residue, where part of your mind remains aware of all the other things you could be checking. Studies show that simply having a smartphone visible on your desk, even powered off, reduces cognitive performance on demanding tasks because some portion of your attention is occupied with not checking the device. This problem is completely absent from traditional memory techniques that require no devices. When you use mental imagery, verbal mnemonics, or other brain-based methods, you can practice anywhere without exposing yourself to the distraction minefield that accompanies all digital learning. The mental clarity and focus you maintain using traditional techniques often translates to better learning outcomes than you achieve using apps, even when the app itself is well-designed, simply because you avoid the attention fragmentation that characterizes all device-based activities in our hyperconnected world.

Building Genuine Mental Capability Versus External Dependence

Perhaps the most profound difference between traditional memory techniques and modern apps involves what you are actually building through consistent practice. When you rely on apps to remember things for you, whether through digital flashcard systems, note-taking applications with powerful search functions, or reminder systems that notify you when to review material, you are essentially outsourcing your memory to an external system. This outsourcing provides immediate practical benefit because the app reliably stores and retrieves information, but it comes with a hidden long-term cost. You never develop the actual mental capabilities that would allow you to remember effectively without the app, which means you become increasingly dependent on your digital tools and increasingly helpless when they are unavailable due to dead batteries, lost devices, lack of internet connectivity, or situations where pulling out your phone would be inappropriate or impossible.

Traditional memory techniques, by contrast, build genuine cognitive skills that become part of your permanent mental toolkit. When you practice creating vivid mental imagery, generating meaningful associations between pieces of information, organizing knowledge into memorable structures, or using rhythmic patterns to encode sequences, you are training your brain to perform these operations more effectively over time. These capabilities remain with you always, accessible in any situation regardless of technology availability. A student who has mastered traditional mnemonic techniques can use them during an exam where phones are prohibited, during a presentation where checking notes would undermine credibility, or in a professional conversation where pulling up an app would seem unprepared or disengaged. The techniques travel with you seamlessly because they exist in your mind rather than residing in a device that might be unavailable precisely when you need it most. Moreover, the mental skills you develop through traditional memory practice often transfer to other cognitive domains, improving your general ability to focus, visualize, create connections, and manipulate information mentally in ways that benefit many activities beyond the specific content you were trying to memorize. App-based learning rarely provides this broader cognitive enhancement because you are exercising the app’s capabilities rather than your own.

Immediate Accessibility Without Barriers

Another significant practical advantage of traditional memory techniques involves their instant accessibility without any barriers or prerequisites. The moment you think of something you want to remember, you can immediately apply a traditional technique to encode it memorably. You need nothing except your own mind, which you always have with you by definition. Compare this seamless immediacy to what using an app requires. You must have your device with you and charged. You must unlock it, likely requiring authentication. You must locate and open the correct app among dozens of icons. You must navigate to the right section within the app. You must input the information, probably requiring typing which is slow and error-prone on phone keyboards. Only after completing all these steps can you actually engage with the learning process, and by then the moment may have passed or your motivation may have dissipated.

This friction matters enormously in practice because learning opportunities often arise spontaneously in contexts where pulling out your phone and navigating to an app feels awkward or impossible. You hear an interesting fact during a conversation and want to remember it. You have a sudden insight while walking that you want to preserve. You are introduced to someone whose name you need to recall later. In all these situations and countless others, traditional memory techniques allow instant encoding without breaking social flow, interrupting your current activity, or drawing attention to yourself. The cumulative effect of being able to capture and encode information instantly across all contexts throughout your day far exceeds what you can achieve with apps that require deliberate separate sessions at specific times in specific places with your device available. Traditional techniques integrate seamlessly into life because they impose zero external requirements, making consistent practice far more achievable than maintaining commitment to an app that must constantly compete with all your other digital obligations and temptations for your limited time and attention.

Powerful Traditional Techniques You Can Master

Now that you understand why traditional memory techniques often outperform modern apps, let me teach you several specific methods you can begin using immediately. These techniques represent the accumulated wisdom of centuries of learners who achieved remarkable memory feats without any technological assistance. Each method leverages different aspects of how your brain naturally processes and stores information, and together they provide a comprehensive toolkit for remembering virtually any type of content you might encounter. I will explain not just what each technique involves but why it works at a neurological level, which will help you apply the methods more effectively and adapt them to your specific needs.

Acronyms and Acrostics: Condensing Information Into Memorable Keys

One of the simplest yet most effective traditional memory techniques involves creating acronyms or acrostics that condense lists of information into easily remembered verbal keys. An acronym forms a pronounceable word from the first letters of the items you want to remember, while an acrostic creates a memorable sentence where each word begins with the first letter of an item on your list. You have probably encountered these techniques before, perhaps remembering the colors of the rainbow through ROY G BIV for red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet, or recalling the order of operations in mathematics through Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally for parentheses, exponents, multiplication, division, addition, subtraction. These examples might seem childish, but the underlying mechanism is sophisticated and applies to any content regardless of subject matter or complexity level.

Acronyms and acrostics work through a cognitive process called chunking, where you compress multiple separate pieces of information into a single memorable unit that occupies less space in your limited working memory. Your working memory, the mental workspace where you consciously manipulate information, can typically hold only about four to seven distinct items simultaneously, which severely limits how much you can remember through simple rehearsal. However, when you chunk multiple items into a single acronym or acrostic phrase, you effectively expand your capacity by treating the chunk as one item that unpacks into many when needed. The key to making this technique work well involves creating acronyms or acrostics that are themselves highly memorable through personal meaning, humor, or vivid imagery. A random string of letters like FPQXZ would not help you remember anything because it has no inherent meaning and creates no distinctive memory trace. However, an acronym that forms a real word or an acrostic that tells a memorable story leverages your brain’s superior memory for meaningful material compared to random information. When creating your own acronyms and acrostics, spend time crafting versions that feel personally meaningful or entertaining to you, because the additional encoding effort and the emotional engagement both strengthen the memory trace beyond what a hastily constructed mnemonic would provide.

Rhymes and Rhythms: Using Sound Patterns for Effortless Recall

Another powerful traditional technique exploits your brain’s exceptional ability to remember patterns of sound, particularly rhymes and rhythms that create predictable structures. You probably remember many rhymes and songs from childhood that you have not consciously rehearsed in years or decades, yet the words come back perfectly when you think of the first line. This remarkable durability reflects how sound patterns engage your auditory processing systems and create strong procedural memories through the rhythm and meter of the language. When information is encoded in rhyme, each line provides phonetic cues that help trigger the next line, creating a self-reinforcing chain where remembering the beginning allows the rest to flow automatically.

You can harness this natural tendency by converting information you need to remember into simple rhymes or rhythmic phrases. Consider how many people remember the number of days in each month through the rhyme thirty days has September, April, June, and November, all the rest have thirty-one, except February alone, which has twenty-eight days clear and twenty-nine each leap year. This rhyme has persisted for generations because it provides a far more reliable and efficient way to remember calendar information than consulting a printed calendar or digital device every time you need to know how many days a particular month contains. The technique works for any information that involves numbers, dates, sequences, or relationships that can be expressed in language. When creating rhymes, do not worry about achieving poetic brilliance. Simple rhymes with regular rhythm work perfectly well and sometimes prove more memorable than sophisticated poetry because their very simplicity makes them easy to rehearse mentally. Many students successfully use self-created rhymes to remember scientific facts, historical dates, mathematical formulas, and other academic content that would otherwise require tedious repetition to maintain in memory. The key is ensuring your rhyme captures the essential information accurately, as a memorable but incorrect rhyme is worse than useless because it will confidently lead you to wrong answers.

The Linking Method: Creating Narrative Chains Between Items

A particularly versatile traditional technique involves creating a story or narrative chain that links the items you want to remember through vivid interactions and transformations. Unlike acronyms that require items to fit conveniently into letter patterns, or rhymes that work best with certain types of content, the linking method applies to virtually anything because you can always create a story connecting arbitrary elements regardless of their inherent relationship. The technique works by leveraging your brain’s exceptional memory for narratives and sequential events, which evolved because understanding stories about social interactions, cause and effect, and temporal sequences provided crucial survival advantages throughout human evolution.

Let me teach you how to use linking effectively through a concrete example. Suppose you need to remember this shopping list: milk, bananas, bread, chicken, tomatoes, and cheese. Rather than just repeating this list verbally, create a bizarre story that links each item to the next through vivid imagery and action. You might imagine opening your refrigerator and having an explosion of milk burst out, the white liquid splashing everywhere. The milk washes over a bunch of bananas sitting on your counter, and the bananas start slipping and sliding around in the milk puddle like they are ice skating. One banana crashes into a loaf of bread, and the bread catches the banana like a baseball glove, cushioning its fall. A chicken suddenly appears and starts pecking at the bread, tearing off pieces with its beak. The chicken then steps on a tomato, which explodes and covers the chicken in red juice, making it look like it is covered in blood. Finally, you grab a block of cheese and use it to wipe the tomato juice off the chicken. This story is silly and exaggerated, which is precisely what makes it memorable. When you later try to recall your shopping list, you simply run through the story mentally, and each image triggers the next item on your list. The technique requires more initial effort than a app-based shopping list, but it builds your visualization and association skills while making you independent of devices that might run out of battery or be forgotten at home.

The Number-Shape and Number-Rhyme Systems: Mastering Numerical Information

Many people struggle particularly with remembering numbers, whether phone numbers, historical dates, prices, or statistical data, because strings of digits lack the inherent meaning and structure that make other information types easier to encode. Two traditional techniques specifically address this challenge by converting abstract numbers into concrete memorable images through consistent associations. The number-shape system associates each digit with an object that resembles its visual form, while the number-rhyme system associates each digit with a word that rhymes with the number name. Once you establish these associations, you can use them to remember any number by converting it into a sequence of images that you then link together or place in a memory palace.

Let me explain both systems so you can choose which feels more natural for you. In the number-shape system, you might associate zero with a ball or wheel because of its circular shape, one with a pencil or candle because of its tall thin form, two with a swan because the number resembles a swan’s curved neck, three with a pitchfork or pair of lips, four with a sailboat, five with a hook, six with an elephant’s trunk, seven with a cliff or axe, eight with a snowman, and nine with a balloon on a string. These specific associations are just suggestions; you can create whatever image-number pairings feel most memorable to you, and indeed creating your own associations often works better than borrowing someone else’s because the mental effort of creation strengthens encoding. In the number-rhyme system, you associate each number with a rhyming word: one is sun or gun, two is shoe, three is tree, four is door, five is hive, six is sticks, seven is heaven, eight is gate, nine is wine, and zero is hero. Again, you can substitute any rhyming words that feel more vivid or meaningful to you personally. Once you have memorized these basic associations, remembering any number becomes a matter of converting it to images and linking them together. To remember the phone number seven-four-three-nine, you might visualize an axe or cliff, followed by a sailboat, then a tree, then wine. Link these images through a brief story: you are standing on a cliff when a sailboat appears, crashes into a tree, and wine pours out from the wreckage. This vivid narrative encodes the number far more durably than simple repetition of the digits ever could.

The Major System: Advanced Number Encoding for Complex Information

For those willing to invest more initial learning time, the Major System represents one of the most powerful traditional memory techniques ever developed for numerical information. This system, which dates back several centuries, converts numbers into words through a sophisticated but learnable coding scheme where each digit corresponds to specific consonant sounds. Once you memorize the digit-to-consonant associations, you can convert any number into words by adding vowels between the consonants, and these words then become much easier to remember and link together than raw digits. Memory competitors who memorize hundreds of digits use variations of this system because it transforms abstract meaningless numbers into concrete meaningful words that leverage your brain’s superior verbal and semantic memory.

The Major System works through these consonant associations, which I encourage you to memorize if you frequently need to remember numerical information: zero is s or z sounds, one is t or d sounds, two is n sound, three is m sound, four is r sound, five is l sound, six is j or sh or ch sounds, seven is k or hard g sound, eight is f or v sounds, and nine is p or b sounds. These associations are based on logical connections that make them easier to learn than arbitrary pairings. The number one has one downstroke when written, similar to the letter t. Two has two downstrokes like the letter n. Three has three downstrokes like the letter m. Zero is the first sound in zero. Five is the Roman numeral L rotated. These and other memory aids help you learn the system relatively quickly. Once learned, you convert numbers to words by selecting consonants corresponding to each digit and inserting vowels to create actual words. The number twenty-five becomes the word nail, because two is n, five is l, and adding the vowel a makes a pronounceable word. The vowels do not matter and can be any sounds you want, only the consonants encode the numbers. To remember the number sequence twenty-five, forty-two, you might visualize a nail going through a rain cloud, because twenty-five is nail and forty-two is rain. While learning the Major System requires upfront investment, the payoff is the ability to remember long numbers, dates, and sequences with far less effort than any other method provides, and unlike an app, this capability travels with you always once internalized.

Combining Traditional Techniques With Minimal Technology

I want to be clear that advocating traditional memory techniques does not mean completely rejecting all technology or returning to some imagined pre-digital past. The goal is reclaiming cognitive capabilities and independence rather than technological puritanism. You can use simple low-tech tools like notebooks and index cards to support traditional techniques without incurring the distraction costs and dependency problems of sophisticated apps. A physical notebook for capturing ideas and practicing mnemonics provides tangible benefits through the motor memory involved in handwriting and the lack of notifications and competing demands that plague digital devices. Index cards for flashcard-based practice offer portability and simplicity without requiring batteries or internet connectivity. The key distinction is between tools that augment your mental capabilities while keeping you in control versus systems that outsource cognitive functions and create dependence. Simple technology that serves your traditional techniques without replacing them represents a balanced middle path between complete rejection of tools and uncritical embrace of every new app promising to revolutionize your learning. Use technology strategically where it genuinely helps without undermining the development of your natural mental skills.

Making Traditional Techniques Part of Your Regular Practice

Understanding traditional memory techniques and even trying them occasionally provides limited benefit compared to making them a consistent part of how you process and store information in daily life. The real power emerges when these methods become automatic tools you reach for naturally whenever you encounter something worth remembering. Let me guide you through strategies for building traditional technique practice into sustainable habits that transform your memory capabilities over weeks and months rather than just providing temporary benefits during isolated study sessions.

Starting With One Technique Until Mastery

When first learning traditional memory techniques, resist the temptation to try implementing all of them simultaneously. This scattered approach typically results in superficial familiarity with many methods but genuine mastery of none, leaving you without reliable tools when you actually need to remember something important. Instead, choose one single technique that appeals to you and feels naturally suited to the types of information you most frequently need to remember, then commit to using only that technique consistently for at least two to three weeks until it becomes relatively automatic and comfortable.

If you often need to remember lists of items like shopping lists, task lists, or sequences of steps in procedures, the linking method would be an excellent choice for focused practice. If you struggle particularly with numbers like phone numbers, dates, or prices, dedicate yourself to learning and practicing the number-shape or number-rhyme system before adding other techniques. If your challenge involves terminology and vocabulary, start with acronyms or acrostics. The specific technique you choose matters less than the commitment to deep practice with one method until you can apply it quickly and naturally without conscious effort. During this mastery period, actively look for opportunities to use your chosen technique throughout your day rather than waiting for major memorization challenges. Use linking to remember your daily to-do list. Create acrostics for items you need to pack for a trip. Convert phone numbers to images using your number system. This frequent practice with low-stakes information builds fluency that will serve you when higher-pressure situations arise. Only after one technique feels comfortable and automatic should you begin learning a second method, using the same focused approach. This patient sequential mastery produces much better outcomes than dabbling briefly with many techniques then abandoning all of them because none became sufficiently automatic to feel useful.

Creating Daily Practice Rituals

Beyond using traditional techniques reactively when memorization needs arise, establishing daily practice rituals that exercise your memory skills proactively accelerates mastery and maintains sharp capabilities over time. These practice sessions need not be long or elaborate; even five to ten minutes of focused daily practice produces substantial improvements in your ability to generate mnemonics quickly and remember effectively. Think of this like physical exercise where brief regular practice maintains and gradually improves fitness far more effectively than occasional marathon sessions.

Structure your daily practice around memorizing small amounts of genuinely useful information rather than arbitrary content that serves no purpose beyond exercise. Each morning, you might create an acrostic or linking story for your major tasks and goals for the day, then recall this mnemonic several times throughout the day without checking your written list. This practice serves double duty by helping you actually remember your priorities while building mnemonic skill. When reading news articles or books, select one or two key facts or ideas and immediately create a memorable encoding using whatever technique you are currently mastering. At the end of each day, review the information you encoded during the day by attempting to recall it without notes, then checking your accuracy and noting which types of content or mnemonic strategies worked best. This brief reflective practice consolidates your learning and helps you identify patterns in what techniques work most reliably for you personally. Some people find it helpful to maintain a small notebook where they record the mnemonics they create and later note whether they successfully remembered the information, creating a personal database of effective strategies you can return to when facing similar memory challenges in the future. The key to sustainable practice is ensuring it feels genuinely useful rather than like arbitrary homework, which means always applying your techniques to real information you care about remembering rather than practicing with random word lists or numbers that have no meaning for you.

Tracking Progress Through Real-World Challenges

Unlike app-based learning that often provides detailed metrics and progress tracking, traditional memory techniques require you to take responsibility for monitoring your own improvement. However, this self-directed assessment can actually produce more meaningful evaluation than automated metrics because you measure real-world performance on things that matter to you rather than gamified scores on artificial challenges designed to feel rewarding. Establishing clear ways to track your progress helps maintain motivation during the skill-building period when techniques still feel effortful and not yet automatic.

Create specific memory challenges for yourself that test improving capabilities in contexts that matter for your life or work. If you struggle to remember names at networking events, set a goal of remembering at least three names at your next gathering using a traditional technique like linking each person’s name to a distinctive physical feature or article of clothing through a vivid image. After the event, assess how many names you successfully recalled and analyze what strategies worked versus what needs refinement. If you need to give presentations or speeches, practice delivering them using traditional techniques to remember your key points rather than reading from slides or notes, then evaluate how well the techniques served you under actual performance pressure. For students, compare your exam performance on material studied using traditional techniques versus material you reviewed through other methods, noting whether the techniques produce better recall of complex information. These real-world assessments provide honest feedback about whether your investment in learning traditional techniques is paying off through improved practical performance, and they help you identify which specific situations or content types benefit most from which techniques. Over time, you will accumulate evidence that traditional methods work reliably for you, which reinforces commitment to continued practice and builds confidence in your memory capabilities that extends beyond specific memorization tasks to affect your general sense of cognitive competence.

When Apps Still Have Their Place

Having spent this article explaining why traditional memory techniques often outperform modern apps, I want to provide balanced perspective by acknowledging situations where digital tools genuinely offer advantages that make them worth using despite their limitations. My goal is not promoting dogmatic rejection of all technology but rather helping you make informed strategic choices about when traditional techniques serve you best versus when apps provide legitimate value. Understanding the strengths and appropriate applications of both approaches allows you to combine them intelligently rather than treating them as mutually exclusive options.

Apps excel particularly at managing large quantities of information that exceed what traditional techniques can handle efficiently, especially when that information requires ongoing updates or organization. If you are building a comprehensive reference library of facts and information across a broad field, a well-designed note-taking app with robust search and tagging capabilities provides organizational power that purely mental techniques cannot match. Digital tools also offer advantages for implementing spaced repetition systems where you need to review hundreds or thousands of items according to algorithmically optimized schedules based on your individual performance with each item. While you could implement spaced repetition manually with physical flashcards and a scheduling system, the automation provided by apps like Anki substantially reduces the management overhead, making consistent long-term practice more feasible. Similarly, language learning apps that provide immediate pronunciation feedback or grammar error correction offer interactive practice opportunities that traditional methods cannot replicate, particularly for learners who lack access to native speakers or tutors.

The optimal approach for most learners involves using traditional techniques as your primary memory strategy for information you genuinely need to internalize and retrieve frequently without external support, while strategically using apps for supplementary functions like organizing reference materials, scheduling reviews of large item sets, or accessing specialized practice opportunities that traditional methods cannot provide. For example, you might use traditional mnemonic techniques to deeply encode the core vocabulary and grammar patterns in a foreign language that you need instant access to during conversation, while using an app to manage a larger supplementary vocabulary list and schedule periodic reviews. You might use linking and number techniques to remember key facts and figures for a presentation so you can speak confidently without notes, while keeping detailed supporting information in a digital note-taking app that you can reference if questions arise requiring specific data points. This combined approach captures the cognitive benefits and independence of traditional techniques for your most important needs while leveraging technological advantages for secondary functions that genuinely benefit from digital tools. The key is maintaining clear boundaries where technology supplements rather than replaces your mental capabilities, ensuring you continue developing and exercising your natural memory rather than allowing external systems to atrophy these crucial cognitive skills through disuse.

“The true art of memory is the art of attention,” observed the 18th century writer Samuel Johnson, capturing a truth that modern learning technology often obscures. Traditional memory techniques force genuine attention and engagement with material in ways that smooth, easy app interfaces can inadvertently prevent. When you must create a mnemonic, construct a linking story, or convert numbers to memorable images, you necessarily attend carefully to the information rather than passively consuming it. This enforced attention produces learning that persists because it was never superficial to begin with, demonstrating that sometimes the old ways remain superior not despite their demands but because of them.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Your Natural Memory Power

As we reach the end of this exploration of traditional memory techniques, I hope you now see that the sophisticated apps filling your phone do not represent the pinnacle of learning technology but rather often sacrifice the very cognitive engagement that makes learning effective in pursuit of smooth user experiences and addictive gamification. Traditional memory techniques that require nothing but your mind, perhaps supplemented by simple pen and paper, frequently produce superior outcomes because they force effortful processing, build genuine mental capabilities, avoid digital distractions, and provide instant accessibility without barriers. These advantages are not theoretical but practical and immediately available to anyone willing to invest modest effort in learning and practicing time-tested methods that served humanity well for millennia before the first smartphone existed.

The essential principles to remember are these. Apps often make learning feel too easy, removing desirable difficulty that produces lasting memories. Traditional techniques build transferable mental skills rather than creating dependency on external systems. Cognitive engagement matters more than technological sophistication for genuine learning. Immediate accessibility without device requirements makes consistent practice far more achievable. Start with one technique and practice it until automatic before adding others. Use traditional methods for information you truly need to internalize while reserving apps for supplementary organizational functions. Track your progress through real-world performance rather than gamified metrics that may not transfer to practical situations. Recognize that mental effort during learning is not a burden to minimize but rather the mechanism through which durable knowledge forms.

Most importantly, begin practicing today by choosing one memory challenge you currently face and applying one traditional technique to address it. Perhaps create a linking story for your shopping list instead of typing it into an app. Convert an important phone number into images using the number-shape system. Construct an acrostic to remember the key points you want to make in an upcoming presentation. That direct hands-on experience with a traditional technique will teach you more about its value than any amount of reading could provide, and you might be pleasantly surprised to discover that methods your ancestors used routinely still work remarkably well for modern memory challenges. Your brain has not fundamentally changed since traditional techniques were developed, which means these methods remain just as effective now as they were centuries ago. The difference is that we have been convinced by technological marketing that newer must be better, when sometimes the opposite is true. Reclaim your natural memory capabilities by rediscovering traditional techniques, and experience the cognitive independence and learning effectiveness that comes from trusting your own mind rather than outsourcing memory to devices that promise convenience while delivering dependence.